“Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.” ― Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

As a very young child, like so many others, my school reading consisted of Janet and John-style reading scheme books. Whilst these undoubtedly helped me develop my reading skills, the plots were a bit dry, and not particularly inspiring. I was fortunate, though, as my parents and grandparents bought me books, and we paid regular visits to our local library. I particularly enjoyed Paddington Bear and The Mr Men Series, and as an older child, I discovered Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl, and other authors whose writing still endures today.

We know that it’s important to get kids reading, but how can we best go about this? Dan Graham, editorial director at Loved By Kids, discusses what makes pupils want to pick up books and immersive themselves in a world of possibilities.

I can still vaguely recall the immense sense of achievement that I derived from being told that I could move on from word cards and could start the school reading scheme. However, excitement soon turned to dismay as my five year-old self realised that years of reading prescriptive and extremely dull books were ahead. The Department for Education's 2012 report 'Research Evidence on Reading for Pleasure' revealed that reading for pleasure is the most important indicator for the future success of the child. Therefore, it seems strange that many school-led forays into our wonderfully rich and diverse world of literature are sometimes so uninspiring.

One of the most common questions put to me when I do training on facilitating dialogues with teachers, especially when they’re secondary school teachers, is: “All this dialogue stuff is great, but how can we transfer all this on to the page?”, or words to that effect. I think the answer lies in the question itself: to transfer the fruits of dialoguing onto the page. But how?

For the last fourteen years I have taught English to secondary-aged pupils at a Pupil Referral Unit in the Midlands. Many of these students are vulnerable and complex, some are in care, and a large number have severe behavioural difficulties. All of this means that we must be especially cautious when choosing a location for school trip. Notwithstanding the risks, last summer I made the decision to take a KS3 group to visit Shakespeare’s birthplace, in Stratford-upon-Avon.

One great part of receiving an education is exploring the world of fiction. James Harlan gives his five best examples for inspiring pupils to put pen to paper (or fingertips to keys…).

“An avenue for learning” – this is the primary offer of most schools. Yet, without bringing it to the fore, catalysing talents is actually another part of the package. The school environment has the immense potential to impact the development of its pupils’ talents, particularly, their gift at writing. The same analogy applies to us teachers.

This April, why not throw a surprise 450th birthday party for Shakespeare, with decorations, cake, the lot? Create an afternoon that will stand out in their memories forever. Inspire them! What could they do with their lives? Shakespeare did not start out with pots of money. He used education, life experience and imagination to create stories we still relate to.

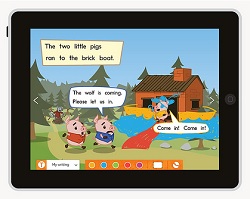

The iPad has been a great tool for teaching children to become better readers.

There are many apps available that parents can use to help their kids improve their reading skills significantly, whether they’re just starting out or brushing up on some basics. Here are some of the best:

Developed by Preschool University, Sentence Reading Magic helps your child read and build sentences. With this app, you can use two learning modes to improve your child’s ability to handle sentences, which makes it a great tool for driving home key reading lessons.

Here is the second article in our series on maximising the use of visualisers across different curriculum areas. We'll be looking at literacy and English classes from key stages one to four.

Use visualisers at key stages one and two to help in building a foundation of basic literacy concepts:

As my role this year involves me teaching across the whole school using a class set of iPads, I feel it is important to really experiment to see how using the iPads can impact across the curriculum and not just within ICT. Consequently, with the Year 5 cohort, I put together a project linking literacy with football. I decided to do this project for two reasons: (1) to see whether using the topic of football can engage the more reluctant boy writers in the class, and (2) to see how well linking digital media and speaking and listening can impact on the children's writing.

As I was working with the classes once a week, the lessons ran over a half term. However, it was the lesson the children looked forward to each week as they were completely enthralled and engaged due to the activities involving speaking and listening whilst using the iPads. I have found that the children's confidence and willingness to write after having the quality time to discuss ideas and experiment leading up to a finished piece of writing had a massive impact on the final product.

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom