Take a moment to think about an ideal school environment.

You might imagine a calm, well-operating and friendly, happy school, where:

Embedding regular singing into school life is a way of ensuring that these attributes develop over time. At Sing Up we have seen countless examples and collected many case studies where the school community themselves believe that singing that has transformed their school.

Looking at it the other way around, it is uncommon to find schools where these ‘ideal’ factors are present and where there is no school commitment to singing, music or another art-form.

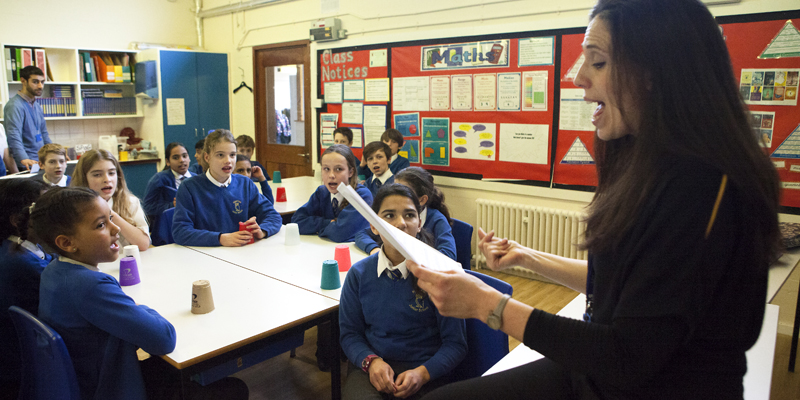

A singing school is a place not just where singing happens regularly, but where singing is right in the middle of school life rather than on the periphery. It is a school where singing is an everyday activity for all children. It is a place where the whole school community knows and can describe the imact singing has in their school.

But changing or developing a school’s culture first requires a change in beliefs and attitudes. Then a renewed focus on music can begin.

For children and their parents

Children and young people are typically more inclined to engage with an activity they enjoy and can see a purpose to – they want to know, what’s the point? So, to truly engage children we could help them further to see the lasting value of pursuing singing and music.

Chorus America’s Choral Impact Study documented the connection between choral singing participation and children’s attainment in the classroom. The study found that children who sing in a choir tend to get significantly better grades than their classmates who don’t take part in choir. A real driver for children of today, who are under high levels of pressure to achieve, could be the fact that taking part in music can have a lasting positive impact on their success in life, whichever career path they wish to follow.

If children understand the continued value of participation in singing and have access to quality provision they’ll quickly become your best advocates for music.

For teachers and school leaders

There is frequently a lot of impassioned discussion about whether the reasons for encouraging and supporting children to sing regularly are fundamentally intrinsic or extrinsic. I would argue that they are both, and that the extrinsic and intrinsic benefits are deeply connected to one another.

Extrinsic benefits might include things like:

While intrinsic benefits might include:

The creative arts – music in particular — are known to have a powerful positive impact on a school environment and on learning outcomes for pupils. And of the musical activities that you can embed in your school most readily and inexpensively, singing is the most accessible of all, and the most adaptable and versatile. Becoming a singing school motivates the school community to work together towards a common goal while taking part in an activity that everyone can do and enjoy.

The quality of the artistic output itself of course cannot and should not be completely disregarded. But as children and young people have a varied natural ability; diverse cultural references and backgrounds; and relative privilege or deprivation, it can be unhelpful to set firm benchmarks of the level they should be able to achieve in their singing or music-making.

What is important is the journey. That you begin in one place, able to do certain things, and then progress to a point where you can do those things better and learn to tackle new challenges with enjoyment and a sense of achievement, rather than anxiety and pressure.

Members of school staff can’t be left out of the picture either. Pretty much all of the best singing schools have some sort of staff singing. The benefits of singing with your co-workers are enormous; it helps you bond, boosts your confidence as a vocal leader, and helps to give all staff the confidence to sing in the classroom.

For all of us – singing is for life!

Singing regularly in a group is beneficial at all stages of your life. Possibly the best evidence for this is that successful people from all industries take time out of their busy days to sing as part of an amateur choir. They’ll spend hours every week rehearsing and will even use precious annual leave time for concert days.

I was fortunate to sing with a wonderful school choir in my teenage years which, clearly, has had a major impact on my career and life-choices! Singing is both a fantastic escape and requires intense focus, which can ease away any stresses from the working day. Mobile technologies and an always-on mentality mean that it’s all too easy to end up working through your evenings, and to not take time out; a choir gives you a ready-made community to spend time with. The bond of singers in a choir is an extraordinary one and friendships made within a choir can be a gift for networking.

Let’s give children opportunities to sing regularly from early years onwards – then not only are we potentially preparing musicians and singers for the future, we are giving them a source of enjoyment, connections, health, and wellbeing for life.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Every September, when greeting my new class, I would follow the same pattern for the first two weeks to settle them in. I don’t think there is anything magical or mysterious about how I settle children and classes, so I am going to share it now, so that anyone can pick up the bits they think they would find useful. I should also give props to my mum here, as I learnt about routine, expectations, and consistent boundaries by watching her as a childminder to toddlers!

Some of you will read this and think “Well, she has never taught in a challenging environment if that works”, but I can assure you that, having worked at inner-city London schools, this settle-in routine was a necessity - not a ‘nice-to-have’ - and there were certainly some very challenging cohorts who I thought this would never work for. But I always persevered, and it always came good in the end!

For me, settling a class is about four main things:

Getting this right in September means not having to be strict all year. I was known for having very high behaviour expectations with my classes. But also, anyone visiting my class to observe during the year could not actually pinpoint what I was doing that they would consider ‘strict’. The reason is very simple: I had done all of my settling back when no one was watching! So now there is nothing to see. They know the rules, and I know what they are capable of.

The introduction

The first thing I would do with my new class is a little speech. Here, I explain that I have three jobs. ‘Teacher’ is my job title, but it is actually my third job once I have completed the first two. The first job I have is to keep them safe. At the very least, your parents expect them all in one piece at hometime each day. Being safe is about the safety of everyone. Individual and collective responsibility. Running around in the classroom = unsafe. Holding scissors aloft while chatting = unsafe. And so on. So any behaviour such as that would stop any lesson immediately (anything which stops a lesson causes a sanction).

My second job is to ensure everyone is happy. This is not to be confused with my job being to MAKE people happy. It is not about having fun or being entertained. Happiness is more a contentment - it means that we care about everyone around us, and show everyone respect in their classroom and learning environment. Someone crying due to someone else ruining their drawing = I need to intervene. Someone upset or angry due to being annoyed by someone else in class = I need to intervene. Again, intervention by me means learning time lost, so could result in sanctions.

The other part of happiness looks at my commitment to intervene - and support/help - if a child is unhappy due to circumstances outside of the classroom. No need to labour this point, but it is worth the pupils knowing that, say, if they arrive angry after a fight with siblings, they can sit and calm down in the book corner before register, to get happy for school.

Once my first job (safety) and my second job (happiness) are done, I can then teach. Those conditions mean we can learn loads. We can discover exciting facts. We can learn about interesting places or words. I commit to always making lessons as engaging and interesting as possible, but making sure pupils learn from them is the main objective. Pupils must commit to working hard and listening, and I will then support them as much as a I can to help them succeed.

Once the speech is done, we usually spend that first lesson drawing up a class agreement based on my speech outlining the above. The rules come from them based on the “safe” and “happy” criteria, ie “We need a rule about hurting people, because that could make things unsafe AND make people unhappy.”

Time to get to work

The next two weeks are carefully planned to include lots of independent working. The reasoning is threefold:

For each of the independent task lessons (at least two a day in the first two weeks) I would, of course, do some teaching up front. After this, I would have various tasks which were very low-challenge or significantly differentiated, so that everyone could access them without support. The tasks quite frankly would be considered, at any other time, to be a total waste of learning time. I make no bones about this. But at this stage in the term, it is vital for me to do this so that for the rest of the year my learning environment allows us to have extremely high expectations.

So during the silent lessons, I will pick up on every single issue of behaviour. I mean every single one. In each case I would never call the child out publicly. While the class works I sit at the desk and work with individuals. I call them over, ask why they think they did the right thing. I will explain my expectations. If it is something a previous teacher allowed but I will not, I explain to the whole class that I understand they were allowed to do that before, but in my class I don’t allow it - and I always explain why, referring to the rules (being careful, of course, not to undermine the previous teacher, but just to say we are different). We set up agreed new routines as a class so that expectations going forward are clear.

Once we have done a few silent lessons the majority of children are now on board and understand that you mean what you say - this is the first turning point. They now start to remind others of the expectations. They start to keep each other on track with other teachers (PPA time) too. Then we can start to spend more time with the more “spirited” children who need a lot more support in settling.

You might even end up spending a lot of time with one or two key characters who seem to be always at your desk during silent working, having been called up for one misdemeanour or another. This time is really key. It gives you a chance to give them attention they clearly need, without it interrupting your main curriculum later down the line. I have had cases where, even right near the end of the two weeks, there is just one or two children I cannot seem to get the right connection with. Some of these go on past the two weeks. But by then, the rest of the class is 100% onboard and actually enjoying how settled and calm their class is. So they do not mind you spending extra time with one.

And this time with the more disenfranchised pupils really works. They eventually realise you mean everything you say. They see you start to loosen up with the rest of the class, and that you really won’t be strict forever if everyone does the right thing. They see you being fair and consistent with everyone. They see you wipe their slate clean and start again every single day. So eventually they trust you, and order is established with everyone. The side effect is also a more cohesive class who work together calmly.

As I said, this may not work for everyone. And in a short article I have had to speed up the explanation, but hopefully the intention is clear and the tips will help some new teachers. Get in touch if you want to find out any more ([email protected]), or discuss any challenges you are facing when settling your class - I am always happy to help!

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Seating plans for a classroom are even more complicated than organising who sits where at a wedding reception. Like so much else in education, you need to define your objectives. It is not just about making sure sworn enemies are not seated side-by-side. Instead, you have to think about the individual needs. Is the child with ADHD better sitting right in front of you, where you can keep an eye on them, or by a wall where they only have a child on one side of them? Is it best to have a child who experiences sensory overload in a quiet area, on a separate single table, or should you put them with a small, sympathetic group who may be able to provide support?

Andrew Moffat is a well-known and respected figure in education. This passionate assistant headteacher made headlines after resigning from a school following a backlash against his sexual orientation and “some of the resource books being used in literacy lessons”. Since then, Andrew has continued to inspire educators as a school leader, founder of Equalities Primary, a speaker and author (No Outsiders In Our School: Teaching The Equality Act In Primary Schools is available from Routledge now).

Is the answer to community reinvention sitting at a school desk? In the year that the UK has appointed the first ‘minister for loneliness’, it seems that perhaps we - as members of a community - need to take some responsibility for anyone struggling within our own locality. Let’s use retirement as an example: it is often seen as a time of happiness, ‘me time’, starting new hobbies, however many issues can hamper the enjoyment - poor health, lack of money, bereavement, distant families, inadequate support and, subsequently, loneliness.

If a child becomes demotivated with their learning, it can become difficult for both teachers and parents to identify the cause. Children often behave differently at home than they do at school, and unfortunately this is not always understood by parents if there isn’t an easy way to see the progression trends themselves. Engaging parents with their child’s education is therefore crucial, so that they can work with teachers together to support child development. Although most will agree with this, there are a number of challenges and disagreements on how the process should be managed.

In a recent assembly at Felsted School here in Essex, I spoke to pupils about the significance of ‘active good behaviour’. It felt like an idea that must have belonged to someone else, an initiative that I was borrowing from elsewhere, but something that was obvious and really important at the same time.

Don’t let your school get stuck in a developmental rut. In the latest IMS Guide - available here - these four disruptive educators share their top tips for doing things a little differently.

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom