With the exam season in full swing, teenagers taking their GCSEs are hoping their teachers covered everything so they can achieve top marks. The methods teachers use in the classroom could also hold the key to improving pupils’ grades, according to a pioneering report published today.

The study, led by the University of Bristol, sheds new light on the fascinating and elusive question: what makes an effective teacher? For the first time in the UK, the researchers have identified which teaching practices drive up exam results and how different class activities work better depending on the subject.

Lead author Simon Burgess, Professor of Economics, said: “Whether or not you have an effective teacher is by far the most important factor influencing pupils’ GCSES, outside of your family background. This unique research unlocks the black box to effective teaching, helping us understand what specific teaching practices are more likely to produce better test scores.

“This is crucial to know as it could also make a dramatic difference to a child’s life chances and their potential future earnings.”

The team of international researchers analysed around 14,000 GCSE results of pupils from 32 secondary schools across the UK, comparing the scores to classroom observation reports spanning two years just before the COVID-19 pandemic on 251 teachers from the same schools.

The research, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, revealed compelling links between GCSE grades depending on teacher effectiveness ratings and class time usage.

The research showed that how teachers used class time had a significant impact on their pupils’ results. In fact, typical variations in class activities between teachers accounted for around a third of the total influence of teachers on the GCSE marks of their pupils.

Highly-rated teachers were also shown to have a greater impact on lower-achieving pupils than higher achievers, a finding with implications for how schools should deploy their most effective teachers.

There were also notable conclusions highlighting how specific teaching approaches are more beneficial for certain subjects.

For instance, the most important activity for English teachers appears to be facilitating interaction and discussion between classmates; more time spent on this tends to raise English GCSE scores. Conversely, for Maths teachers, the key activity is making time for pupils to practise questions individually in class; again, more time on this increases GCSE marks.

Assessing the long-term impact, the researchers went on to project how such improvements would enhance pupils’ future salaries. The effects are sizeable: the typical change in class time use considered raised GCSEs and later salaries that generated an additional £150k of lifetime income every year for a class of 30 pupils.

The report, in collaboration with the Oxford Partnership for Education Research and Analysis (OPERA) and Harvard University, forms the basis for a cheap and easy tool which teachers and school leaders can use to identify and improve classroom skills.

Professor Burgess said: “The potential of these findings is huge in both educational and economic terms. This greater understanding of the most effective teaching techniques could be used to help teachers learn and improve their own performance.

"Now we know the added importance of effective teaching for lower-achieving pupils, the research could also be used to inform and advance the ‘levelling-up’ agenda, helping underprivileged pupils thrive.”

This week testing season officially begins. Edtech products can play an important role in students’ preparation for exams, as well as supporting extending learning beyond the classroom throughout the year. Here are 11 edtech products helping to ease the pressure on students and teachers at what can be a stressful time of year.

This week thousands of students across the country are sitting down to take their first GCSE exams. Your students need to walk into the exam hall with plenty of knowledge to draw on but, in a packed curriculum across a wide range of subjects, even the most able students can have a hard time recalling the mountain of knowledge needed.

So how can you ensure that students retain an in-depth knowledge and understanding of concepts studied, in some cases, as early as the beginning of Year 9?

The answer lies in harnessing the power of their long-term memory through retrieval practice – and it isn’t as hard as it sounds.

Use it or lose it

Our brains are in the habit of forgetting: there is a lot of unimportant information we take in day to day that we don’t need to store. But, if we want to retain a certain piece of information, we need to work to transfer it to long-term memory. The best way to achieve this is by training ourselves to remember it with repeated recall. By doing this we give our brains the signal that this information is something we need and therefore it should be stored securely and accessibly. Passwords and phone numbers are a good example of this effect. Those we use a lot are regularly brought to mind and well known to us. Those we don’t need as often are all too easily forgotten.

This is the idea behind retrieval practice, which is becoming increasingly popular in schools. Cognitive psychologists and educators alike agree that the very best way to combat forgetting and make sure students can access knowledge when they need it, is to ensure they practice recalling it regularly. This means that by starting revision from day one, your students will be going into the exam hall with much more knowledge at their disposal.

Reap the benefits

The benefits of retrieval don’t stop with knowledge retention; it also goes a long way to improve students’ attitudes to assessment.

In a survey published by Washington University in 2014, retrieval practice was shown to significantly decrease test anxiety when used by students aged 11-18. By including regular low-stakes testing with immediate feedback throughout the academic year, 72% of students reported that they felt less nervous for their exams.

As regular retrieval becomes the norm, your students will not only remember more of the information retrieved but will also become more aware of their learning: what they do and don’t know. Frequent low-stakes testing helps students to understand that it’s not enough to just listen in lessons: they have to engage with the content too.

Make retrieval easy

There are a multitude of ways you can get students recalling learning throughout the year, but it can be hard to find the time to do so. Any practices which take place in the classroom are inevitably competing for time against other activities and it can be hard work to keep them up consistently all year. Low-stakes testing and multiple-choice quizzing are highly effective for this purpose, but anything which requires marking is also unlikely to make it into your everyday practices.

If you want to make successful use of retrieval practice throughout next year, edtech is your best bet for implementing it in a realistic and effective way.

By making online tests a regular part of homework, you can ensure that students are efficiently and consistently recalling key knowledge, so they retain significantly more of what you have taught. By assigning work which self-marks and shows students the correct answers straight away, not only will you save marking time, but you will also be able to reinforce what’s been retrieved and, crucially, make sure that any false assumptions are immediately corrected.

By embedding retrieval into your teaching and homework policy, effective revision can be carried out all year round. Students won’t be able to hide from what they don’t know and will increase in engagement and confidence as they see their foundation of knowledge building.

Doddle is currently available for an exclusive classroom trial and discount through Edtech Impact.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Another school year is upon us, with GCSE season a recent memory: a period in the school calendar that, as ever, brought stress, anxiety and a lot of prayers. Year on year, the same patterns emerge in a relentless bid to ensure that the pupils are the best that they can be, leaving schools in ‘stuck record’ syndrome.

You can picture the scene: frantic teachers throw everything possible at pupils through endless interventions, worksheets and helpful strategies whilst the nonchalant pupils happily coast lackadaisically before reality sets in, leading to late night cramming sessions. But it’s all worth it, as we see Year 11 pupils enjoying their summer and teachers enjoying the extra time to catch up on the piles of work forgotten in the past month. The late nights, the arguments and the tears (mainly from the teachers) are forgotten, and we subconsciously prepare to do it all over again.

And yet, what is the real toll? Everyone is exhausted and, although, cramming may lead to a short-term gain, it leaves pupils less prepared for college and beyond. Pretty much, cram means can’t retain and master. Every year we think something has got to change to support the sanity of pupils and teachers, but the short-term pain becomes lost when pupils show a glimmer of success and progress, making it seem worthwhile.

So, the cycle continues, the GCSE season is back and all the reflection and “never again” resolutions quickly evaporate. It’s like having Dead or Alive’s cult hit You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) playing in the background. But we can change the tune by not waiting until next year to cram, but by starting right now, with revision utilising the spacing effect.

“The spacing effect is one of the oldest and best-documented phenomena in the history of learning and memory research.” (Bahrick & Hall, 2005)

Numerous studies provide evidence to suggest that spacing learning out has a greater impact in learning than massed study. More so, spaced repetition improves a person’s ability to retrieve information from memory.

Our current method of cramming during GCSE season may appear to have a short-term impact but learning from those sessions won’t stick. Instead, a steady, regular approach over time is necessary to improve learning and retention. Therefore, pupils who start preparing for next year’s GCSE now not only improve their results, but will be able to carry their learning with them to the next phase of their schooling or work life.

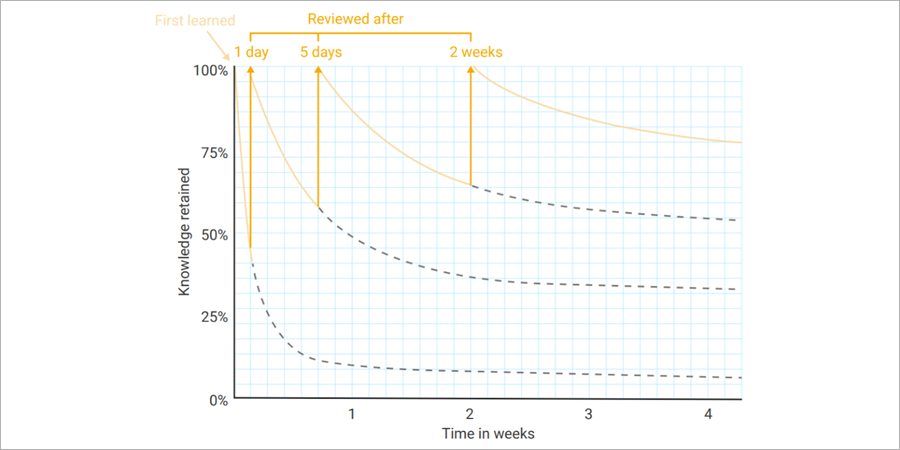

A classic study by Ebbinghaus suggests that new learning quickly erodes nearly 70% after one day and is nearly forgotten after one month. Unfortunately, knowing this probably does little to alleviate the frustration we have sometimes when pupils’ primary response in the next lesson is “I don’t remember!” But what it does demonstrate is that teaching without revisiting material will only lead to panicked, last-minute anxiety and cramming when the month of May approaches.

Here are three (of many) practical ways to embed the spacing effect in the classroom:

1. Use of low-stakes formative assessment strategies, such as quizzing, to regularly test key concepts spaced throughout the year.

2. Develop subject level revision mapping to ensure key concepts and topics are interleaved to support pupil home learning.

3. Find opportunities to revisit prior learning by making explicit links with new learning.

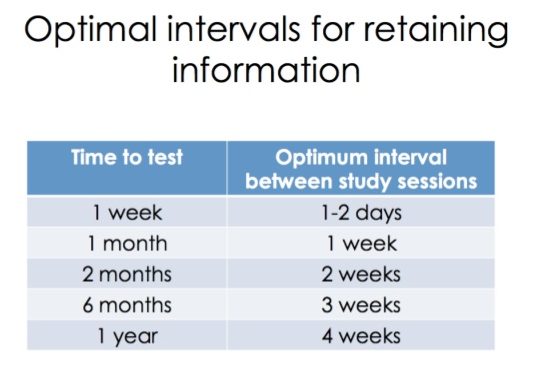

There are many ideas when it comes to when and how often to put the spacing effect into practice. However, Cepeda et al (2008) provide a helpful recommendation on the optimal intervals to maximise the potential of the spacing effect.

It may be hard to digest that, to learn, we must be on the verge of forgetting. However, it is time we changed our thinking. Helping pupils to stop cramming will always be difficult, but we can help by considering the spacing effect in our curriculum planning. Even more, we must improve pupils’ revision skills so that they know when and how to study.

Cramming may work in the short term, but for learning to last steady, regular, spaced learning needs to take place. The impact of the spacing effect is more than improving pupil attainment; it will also help pupils’ learning to stick.

References

Bahrick, H.P. & Hall, L.K. (2005). The importance of retrieval failures to long-term retention: A metacognitive explanation of the spacing effect. Journal of Memory and Language, 52, 566-577.

Cepeda, N.J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J.T. & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning: A temporary ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological Science, 19, 1095-1102.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Proposing the idea that more testing may be the answer to improving pupil outcomes would undoubtedly result in heads in the staffroom turning in absurdity - or the cause of a full riot on social media. It is the belief of many that pupils are being over-assessed already, so why introduce more? It is felt that too much assessment is affecting the mental health of children, or squeezing the joy out of learning, and may be a direct cause of underachievement. Therefore, to introduce more would be outlandish. Each concern is valid - especially in the case of high-stakes testing - however, we should not discount the role that low-stakes testing may have in enhancing pupil learning.

When it comes to traditional subjects - the ones that have been taught and used effectively for centuries without the use of technology - the co-existence of old and selective use of the new seems to be the best way to innovate the curriculum. As we get to grips with the ‘new’ GCSEs and learn more about the workings of the mind and memory, check tests, dual coding, factual recall and retrieval practise are all making a comeback.

Have you ever had a song stuck in your head for what seems like days? The same words and melody looping over and over again? While it might be frustrating, your brain is actually doing some really amazing things as you recall Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance for the hundredth time that day. When a song gets stuck in your head it may have something to do with our involuntary memory, which encodes music in many different ways, helping us to remember a tune we’ve only heard once at our niece’s 11th birthday party. It’s a powerful concept; try applying this to an educational setting, and we can achieve considerable results.

When asked about the most memorable songs of all time, what springs to mind? The Killers’ Mr Brightside, Britney Spears’ Baby One More Time, or Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean? There are so many songs that no matter how much time has passed, you’re able to sing-along to every lyric without hesitation.

Progress 8 marks one of the biggest shifts in the way we evaluate the success of students and schools. Love it or loathe it, it looks set to stay. And while we recognise that it will take a few years to stop focusing on headline A*- C grades, the need to demonstrate pupil progress across the entire spectrum is now far more important than just being able to shout about exam success.

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom