The language errors above are on purpose! Imagine such an EAL learner going from lesson to lesson – History, Maths, Science – and at each point being bombarded with different types of language and thus different types of academic literacy. In period 1, History, the student was exposed to Past Simple, being asked to write a story about what happened during the War. In period 2, she was told that word problems are similar to stories, but then why exactly is it that such stories are written in Present Simple (“buys” instead of “bought”)? And finally, Science is full of passive voice phrases (“is made”, “is formed”, “has been done”), grammatically difficult structure, composed of what looks like two verbs: 1 – “is”, 2 – “made”. It is in fact a passive voice structure consisting of the verb “to be” (is) and past participle of a verb (“made”).

The academic literacy / language in these three subjects is a source of significant confusion to our Latvian learner!

We are told to, and most of us certainly do, teach Literacy across the curriculum, but what precise literacy are we actually supposed to teach? Have you considered before that each academic domain and each school subject comes with its specific academic literacy, meaning that the language requirements of your subject – for instance, History or Science – are very different?

If teachers don’t pinpoint what English academic literacy skills that a subject actually requires, and what language conventions exist, then students such as Diana are at risk of being confused and won’t be able to access your content. Your course books and most likely your own speech, determined by the conventions of your domain, are full of such subject-specific language, and that language needs to be taught to your students. A good start into the research on academic literacies is reading Lea and Street’s 2006 journal, The Academic Literacies Model: they write about three approaches to student academic writing, of which academic literacies appears to be the most nuanced and sophisticated.

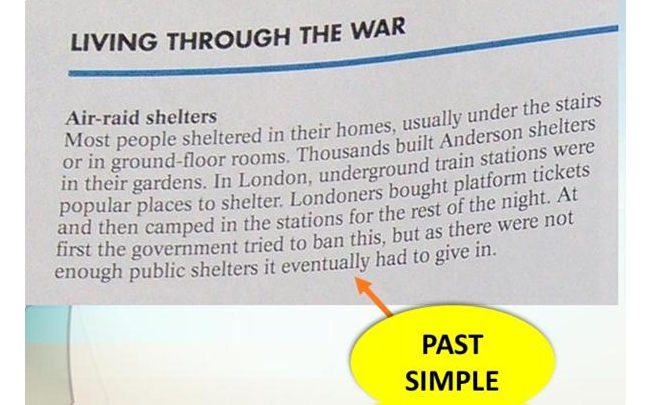

Academic Literacy 1: History

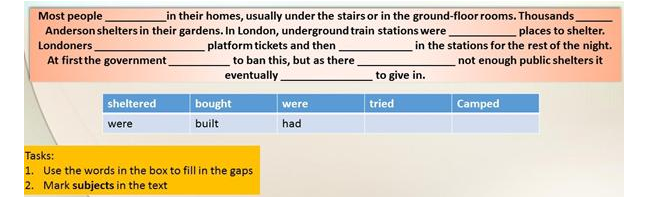

Let’s just have a look at three specific examples from real UK-based books. The one on the right is from Shephard and Shephard’s 2007 History textbook Re-discovering the Twentieth Century World: A World Study After 1900.

So many past simple forms here – “sheltered”, “built”, “bought”, “tried”. Past Simple emerges as the main grammatical feature of such a text, and in order to be able to write within this genre, students need to be able to use its regular and irregular forms.

Academic Literacy 2: Maths

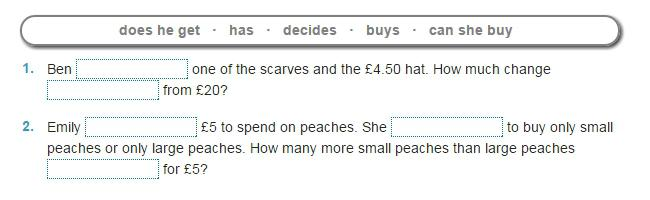

The language of word problems is a linguistic genre of its own. What confused Diana in Maths was that it was presented to her like “a story”. It certainly looked and read like one – but it’s not told in the past simple, the way the History story above was. The vast majority of verbs in Maths are in the present simple tense (“buys”, “does she get”, “has”, “decides”), and this is likely to be the grammatical / linguistic area that needs to be taught to learners!

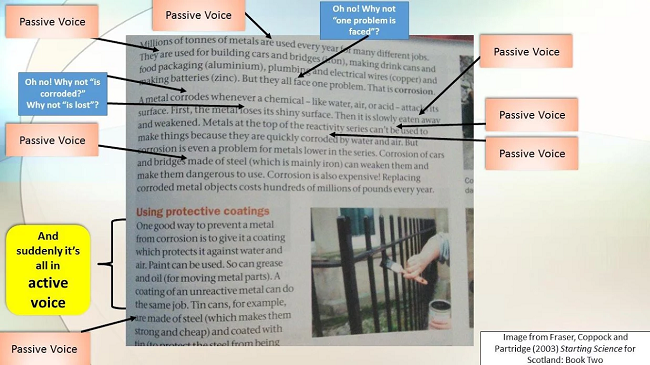

Academic Literacy 3: Science (oh boy!)

The language requirements of Science are what a friend of mine would call “un-fun”. As you will see from the image below, it is the understanding of the passive voice structure that is required here. These are the phrases such as “are used”, “is eaten”, “are made” – which emphasise what is done rather than who does it. As such, they’re different to active voice sentences (eg Acids eat metals away), and represent a very complex piece of grammar to learn. Science texts are full of exciting structures like that – and challenge EAL learners.

WHAT DO WE DO, THEN?

You might be thinking: “What do I do with all these language requirements? I am not a language teacher!” You are in luck, though, as your friendly EAL specialist comes to the rescue! The answer is DARTs – however, don’t rush to your local pub for a round of pub quiz and a game of darts just yet! DARTs stands for Directed Activities Related to Texts. They are the type of activities that focus your students’ (all of them, not just EAL) attention on the language within your content texts. They could be gap fills, cloze activities, jumbled up sentences, matching halves of sentences to create full sentences, labelling pictures, categorising items. I strongly recommend that you watch YouTube video on DARTs, which advises on the use of DARTs more extensively:

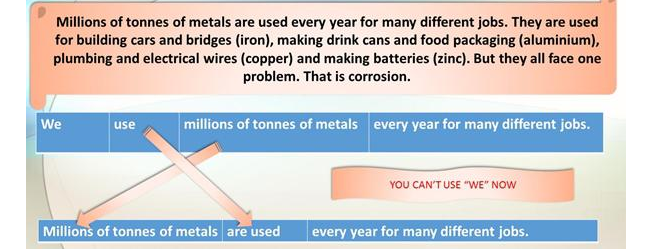

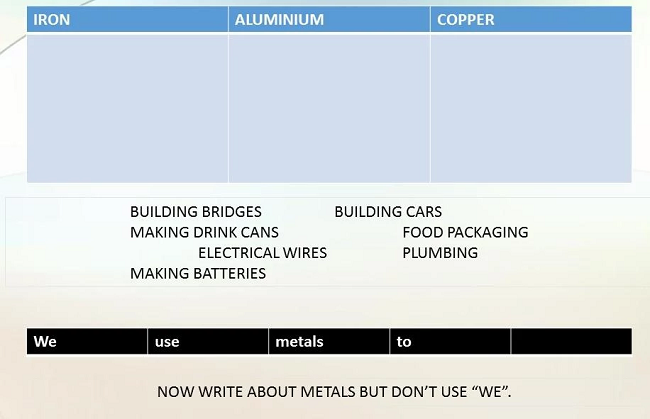

In the meantime, let’s have a look below at how we can approach the teaching of passive voice for Science. The blue table shows how you can use what is called substitution tables (each column represents different part of a sentence: subject, then verb, then object) to teach students how to change active voice into passive voice. This shows how the object in the active voice sentence (“millions of tonnes of metals”) becomes the passive voice sentence’s subject, and how “use” becomes “are used” and how “we” disappears in the passive voice sentence. All presented visually in line with the distinctive EAL pedagogy.

Of course, you want your learners to write about your content. Get them to categorise what those metals “are used” for, and then follow it up with a simple substitution table (first activity below), but at the end, prohibit them from using the word “we” so they have no choice but use passive voice structures.

And that’s how you get your students to understand and write in the Science vernacular! Now, let’s look at our History lesson again. How do we ensure that our learners focus on the Past Simple tense, required to write recounts of historical events? Simple! See below! We provide a gap fill, but rather than focus on the content, we purposefully pick our language aspect: Past Simple. As you can see below, I’ve removed all the past simple verbs from the text and provided them in a box. (Of course, you can simply differentiate for your students by not providing the box with words if you feel that some of them would be able to tackle such a task without it.) I also follow this activity up with getting the students to highlight/mark the subjects in the text that will always precede the verbs, teaching them the structure of past simple affirmative sentences.

You could prepare a very similar exercise for the Maths content, only this time you would focus on the present simple tense, specific to the word problem genre of text.

Summing up

Recognition is needed that academic literacy is not just one, but is composed of the awareness of numerous literacies across various academic domains. The first step is realising this and spotting what language requirements do exist in your own subject. Once done, you can certainly try out DARTs to create activities to enable your students’ access to the content you want them to learn. Without this linguistic differentiation for your literacy-struggling students, I am afraid they’re simply not going to be able to produce results.

A long time ago, Pauline Gibbons (1993) provided a wonderful metaphor that explains this: a competent language user may perceive it to be window – transparent and difficult to see. For children with poor English skills, the same window is made of frosted glass – it’s a block to learning. Do notice the specific academic literacy within your subject and do use DARTs to allow them a way in to your content. If you do, they will surprise you with what they can do. Very pleasantly.

References:

Gibbons, P. (1993) Learning to Learn in a Second Language. Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, Australia

Lea, R. and Street, B. (2006) ‘The “Academic Literacies” Model: Theory and Applications’, Theory into Practice. Vol.45(4), pp. 368-377

How do you handle these areas of literacy? Let us know below!