"I was very unsure of how my first lesson would go, whether the students would quickly make the links."

In the past, I have had experiences of teaching reading programmes, aimed at boosting the reading ages of students in schools. They seemed to work well, providing all learners with a window in which they have to read. However, I always wondered what else could challenge the More Able cohort, who already have high reading ages and regularly engage in reading outside of the classroom. The concept of Latin seemed to somehow fit.

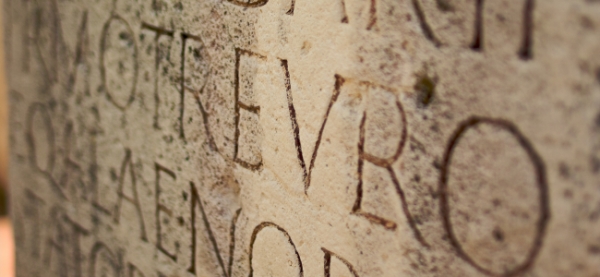

The course I am introducing focuses on the processes of translation from Latin into English, a skill Year 7 students will more than likely not have experienced, and reading texts. I was very unsure of how my first lesson would go, whether the students would quickly make the links, whether they’d have a high enough level of literacy to be able to look at a Latin sentence and deduce meaning from the use of their own English vocabulary.

To try and arouse some form of relevance to the students and their studies, I kicked off the lesson by showing the historical change of some words from Latin into Italian, Spanish and French, as detailed below:

FURNUS oven (Latin) > forno (Italian) > horno (Spanish) > four (French)

Taking a deep breath, closing my eyes and wondering if my planning was completely flawed, I asked the students to try and think of some words in English that could derive from Latin. The responses I got simply blew my mind.

The first answer I got was “inferno”, followed by “agriculture” and “Luke”. Luke was a word that arose my interest, which naturally led to a discussion of what the word meant, what its origins were, culminating in me having to explain the importance of the bible as a source of evidence for linguistic study due to a student telling me he thought it was Latin due to its use in the bible (true, as “LUCAS” was the Latin for Luke, coming from the word “LUX” - light).

Following on from this, I got my students to wander around my room and find the Latin translation for a set of English phrases. I noticed a lot of students reading words aloud and taking a risk - guessing the associated English definition by piecing together, from their English linguistic bank, possible meanings.

As a GCSE MFL teacher, trying to help students look at words and piece together meaning through lexical deduction is a constant battle, but this top set group seemed to grasp the idea and this new way of thinking very quickly.

Coming back to the usefulness of Latin as a way to improve literacy, I want to take you back to the developments of our own language. When William the Conqueror arrived, French became the language of administration and law, with academics favouring the French-influenced English to the Anglo-Saxon English. I believe, when faced with more demanding texts where students aren’t fully sure of the meaning of words, the skills of deduction through looking at words lexically will help students boost their understanding and deduce meaning, boosting their understanding, thus their reading ages. Therefore, I believe such an ‘archaic’ and ‘dead’ language has a very worthy place in the classroom in 2015.

Do you teach Latin? Share your experiences below!