"Schools, as service providers accountable to both society and Ofsted, have to decide whether to cling to traditional values of academic excellence or to embrace progressive, technology-driven, individualised learning."

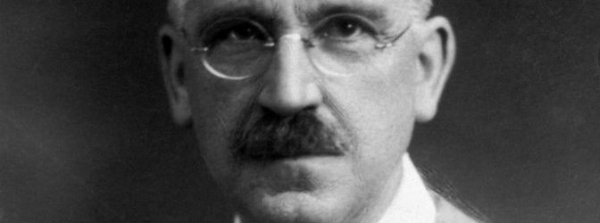

Pragmatism is a school of thought that emerged primarily from the writings of three American thinkers: the natural scientist and philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1842-1910), the psychologist and philosopher William James (1842-1910) and the philosopher, psychologist and educationalist John Dewey (1859-1952). (Biesta and Burbules, 2003)

All three of them believed that academic philosophy had become too abstract and academic. They thought that philosophy should be a spur to social change and should be informed by society. That it should deal with the problems of men, not the problems of philosophers. They also predicted an epistemological model of socially-constructed knowledge that has become relevant to the current time due to the explosion of the World Wide Web and personal digital technology.

Dewey’s most enduring influence is in the field of education. He believed in the unity of theory and practice, not only writing on the subject but for a time participating in a progressive ‘laboratory school’ for children connected with the University of Chicago (Dewey, 1938).

He attempted to reconcile the gulf between traditional and progressive education by using a robust philosophical framework to promote a more ‘intelligent’ way of working. At the time his writing was hailed as a guiding beacon for a society that was experiencing rapid social, cultural and economic expansion.

So today perhaps, we find ourselves in a similar situation; the education of our children needs to prepare them for a world that is undergoing an economic, technological and cultural metamorphosis. Schools, as service providers accountable to both society and Ofsted, have to decide whether to cling to traditional values of academic excellence or to embrace progressive, technology-driven, individualised learning. My focus of this article is to ask: is there a pragmatic solution, a middle ground that Dewey would recognise if he were to visit our school today?

Innovation in schools might be seen as the movement from a traditional model of education towards a progressive model. One of Dewey’s contributions was to characterise these two approaches and put forward the idea that progression should not be merely a negative reaction to tradition. He deplored the necessity for pupils taught in a traditional manner to be docile, passive, receptive and obedient (Dewey, 1938) but did not feel that the opposite extreme was desirable either:

“Impulses and desires that are not ordered by intelligence are under the control of accidental circumstances… A person whose conduct is controlled in this way has at most only the illusion of freedom. Actually he is directed by forces over which he has no command.” (Dewey, 1938)

Dewey acknowledged that teaching in a way that built on the existing experience of the learner, that did not oppress them or impose unnecessary restrictions, required a well thought-out philosophy and well planned activities:

"It is, accordingly, a much more difficult task to work out the kinds of materials, of methods, and of social relationships that are appropriate to the new education than is the case with traditional education."(Dewey, 1938).

The main significance of Dewey’s pragmatism for educational research is that he deals with questions of knowledge and the acquisition of knowledge within the framework of a philosophy of action.

Dewey made it clear that the domain of knowledge and the domain of human action are not separate domains but are intimately connected; that knowledge emerges from action and feeds back into action and that it does not have a separate existence or function.

Perhaps, then, he would be impressed to see how active learning techniques, technology and traditional teaching skills are being used together to create zoned learning, project-based learning and individualised learning pathways at Homewood School And Sixth Form Centre (HSSC), where we have had a 1:1 mobile device scheme for students since 2004.

One of the characteristics of pragmatism as a guiding framework is that it is concerned with ‘what works’ in practice. The use of targeted research projects, student questionnaires, parent surveys and dedicated departmental planning time have all contributed to the ongoing cycle of curriculum development and review at the school. The delivery of Key stage 4 sciences, as zoned learning, was created around a vision of an active learning approach. It aims to foster the skills of teacher-independent inquiry and investigation. Students were surveyed after the first year and their feedback used to develop the way that zoned learning was delivered. A balance between teacher led ‘chalk and talk’ and independent learning was found to create the best learning environment, avoiding student frustration at not being able to progress but stimulating engagement at the same time.

New teaching techniques for group cooperation such as the Kagan (Kagan, 2009) approaches have supported learners in developing their independence from teachers as the ‘sage on the stage’ and develop enhanced social skills to promote enjoyable learning. These skills are shared with staff as part of a comprehensive staff-training programme with regular weekly sessions.

In the new Key stage 3 programmes, now known as Discovery College, Dewey would be thrilled to see that learning through action takes a central role. Rather than teachers delivering a scheme of work written by an external company, the staff are using their pooled experience to develop a project based learning curriculum that sees collaborations between Science and PE one term and Science and Maths the next. The aim is to have an authentic audience for the final project to give the work purpose and relevance.

"The use of targeted research projects, student questionnaires, parent surveys and dedicated departmental planning time have all contributed to the ongoing cycle of curriculum development and review."

The evolution of the 1:1 scheme saw the introduction of the student iPads in 2012, and as result student cohorts in year 7, 8 and 9 are able to access resources, applications and presentation tools as part of their learning pathways. The scheme was further extended to include Key Stage 5 students in 2014. The introduction of the student iPad scheme has meant that the current cohorts in year 7,8 and 9 are able to access resources, applications and presentation tools as part of their learning pathways.

The use of iPads has been one of the aspects of innovation at HSSC that has highlighted the need to reconcile traditional and progressive approaches to education. Some published surveys (Heinrich, 2012) have had a positive bias towards the benefits of introducing iPads, and by using closed questioning techniques have imposed a framework of values upon the respondents. At HSSC, the impact upon staff has been investigated with an internal research report (unpublished at the time of writing) and the impact upon parents was recently surveyed by the e-Learning Foundation. If as Dewey suggested, ‘All social movements involve conflicts which are reflected intellectually in controversies’ (Dewey, 1938), then the debate, which is stimulated by the adoption of a new technology, is both healthy and necessary for ‘intelligent’ and informed growth.

It is not surprising that some teachers and parents fear the changes and loss of control over their student or children’s access to knowledge that ubiquitous mobile technology can bring. The balance between retaining traditional skills and cultivating new ones is part of the pragmatic approach that is being adopted in our curriculum development.

If, as part of a GCSE physics project into time travel, we were able to bring Dewey on a visit to HSSC as our new School Improvement Partner, I hope he would be encouraged to see that by avoiding unnecessary extremes of progression or tradition, by working with reflection and research based curriculum development and by embracing the potential of new technology we are truly learning through action, putting theory into practice and changing practice based on experience.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: BIESTA, G. & BURBULES, N. C. 2003. Pragmatism and educational research, Rowman & Littlefield Lanham, MD. DEWEY, J. 1938. Experience and Education, New York, Touchstone. HEINRICH, P. 2012. The iPad as a tool for education. A study of the introduction of iPads at Longfield Academy, Kent. http://www.naace.co.uk/publications/researchpapers: Paul Heinrich & Co Ltd (Educational Consultants). KAGAN, S. K. 2009. Kagan Cooperative Learning., San Clemente, CA:, Kagan Publishing.

![]() Looking for more resources to support your teaching and learning? Check out the best education technology resources on our sister platform EdTech Impact.

Looking for more resources to support your teaching and learning? Check out the best education technology resources on our sister platform EdTech Impact.