We have had a ‘skills-based’ curriculum where knowledge is second to its application. We could show ‘outstanding progress’ by giving students a task at the start – applying a ‘treatment’ (which essentially was some knowledge so they could understand the source) – and then as if by magic they could use their skills on a higher level. The obvious issue is that skills had not been developed, but that the content had allowed students to demonstrate skills they were already capable of. Following that, thematic modules looking at change over time became all the rage.

More recently this has given way, in part linked to the new 9-1 curriculum, to a knowledge-centric curricula where knowledge is king. Some “Every lesson has differentiated outcomes.”decry “how can someone possibly talk about the reasons why an event happened if they haven’t first grasped what has happened?” This has been coupled with the necessity for students to have their historical progress mapped over a five or seven year period. Some schools have transformed schemes of work into ‘programmes of study’ or ‘schemes of learning’. Here, every lesson - and every task within lessons - has differentiated outcomes, and the aim is that you could walk into five History classrooms on the same day with the same year group and find the same lesson activities and outcomes being delivered.

For me, however, this need is not driven by the students but by those looking to hold teachers accountable, and its clinical edge is driving creativity and inspiration out of the classroom. History is a magical subject which can ignite passion and enthusiasm from me. Some History topics, however, are dull. Conversely, what I find dull, some find engaging - where I am impassioned, they are not. It is by its intrinsic nature subjective.

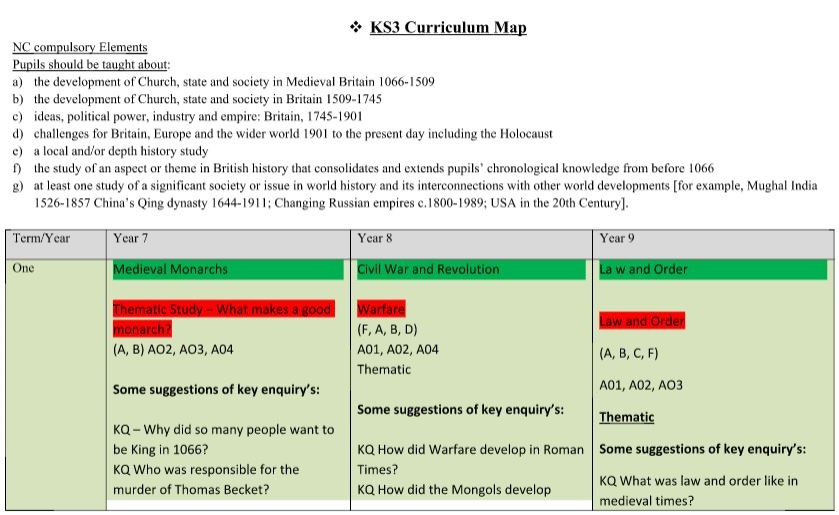

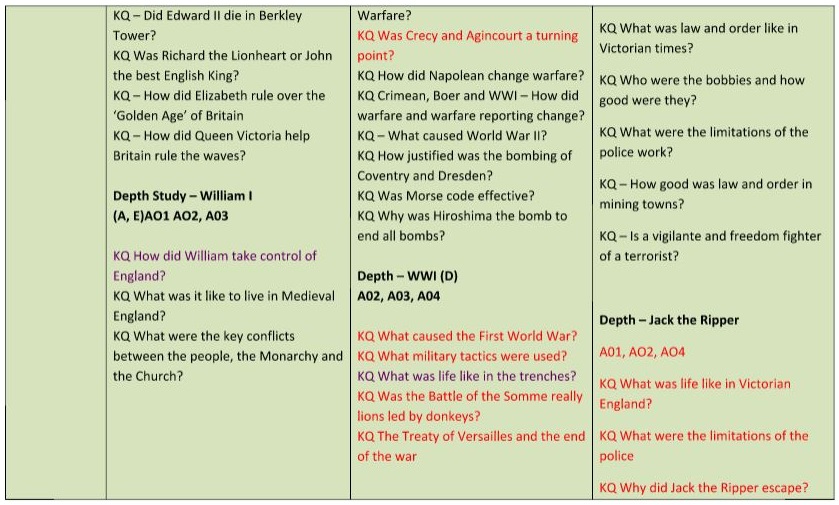

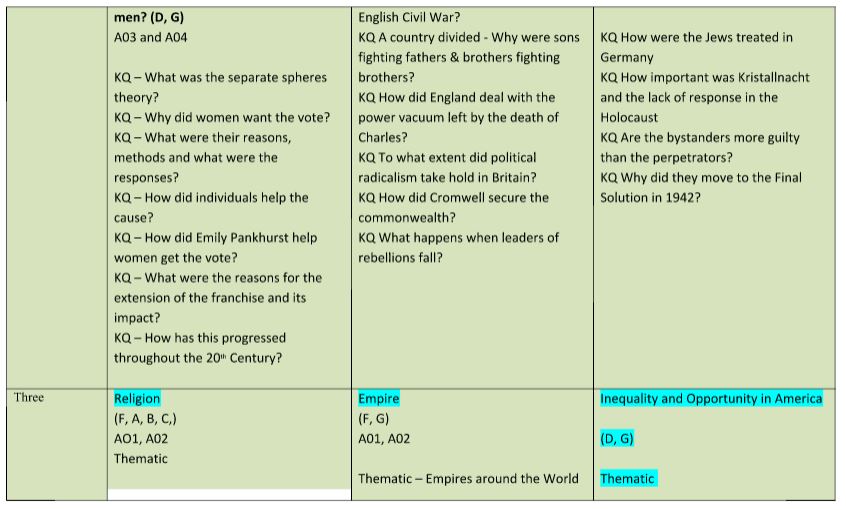

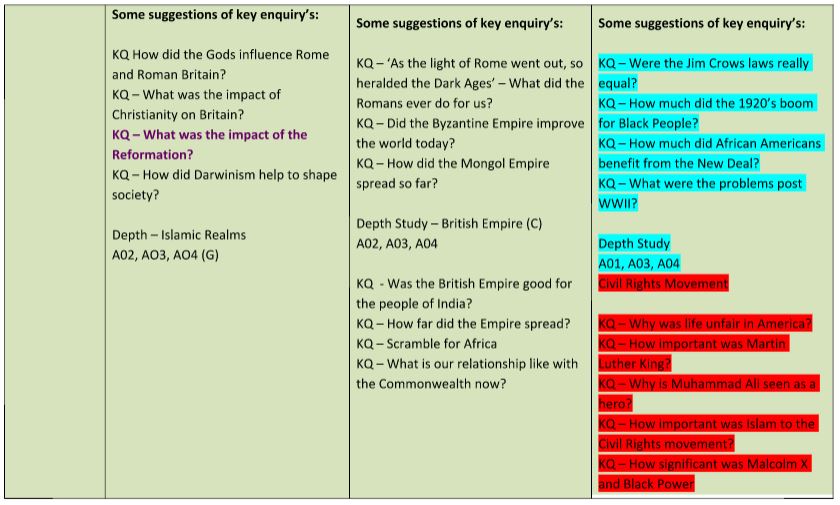

Therefore, what I developed at my school is a curriculum that allows individual teachers to follow their passions, and also balances both skill and depth of knowledge. For example, students might look thematically at issues of power and the people (chosen by their individual teacher) before an in-depth study focus on the Suffragettes. Or their teachers chooses a selection of revolutions over time (Spanish Civil War, Russian, French, American etc) before a half term spent on the English Civil War. For example:

Example KS3 Curriculum Map

This approach can cause concerns about how to accurately weigh and measure both student and teacher progress if they are following different content to their peers and colleagues. However, as long as your assessments allow for an option (such as ‘Choose two revolutions you have studied - how similar were they?’), and the mark scheme requires the same level of knowledge for each topic, then their education should be the same as their peers.

The potential downside is that, by allowing teachers to teach to their passions, you may have insufficient knowledge to challenge them, and may not be able to quality assure the delivery of every lesson in your department.

However, the upside is that by giving the trained professionals license to follow their passions, they will teach better lessons. They will be able to bring the little snippets of wider knowledge that enlighten a source or interpretation. More children will fall in love with what is the best subject to teach.

To conclude, for me the best curriculums are not ones that prioritise enquiry, knowledge or skills over one-another. They share the same importance. “Individual passions are given free reign to burn brightly.”This isn’t a scenario where you can map the skills and content delivered in Year 7 lesson one, then show how students have contributed to outcomes in Year 11 on a pure, linear assessment line. It is one where the individual passions that subject teachers have for their subject are given free reign to burn brightly, because this tactic gives a far better chance of lighting the torch of our future historians (or whatever jobs each subject can lead to), than a teacher who has only a dying emblem of a flame for a topic trying to inspire the next generation.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!