The Theory of Marginal Learning Gains brings together many sources of inspiration and thinking and can be used to inform and shape a focused whole-school approach to coaching programmes and the design and implementation of school action research projects.

“Tiny Changes, Big Difference”

The Theory of Marginal Learning Gains hones in on just a selected number of tiny elements of teaching. Applying Marginal Learning Gains Theory gives a route into the complexities of learning. After all, the complexities of teaching reflect the complexities of learning and there’s a real beauty in that. Using Marginal Learning Gains as a way to analyse the ‘Why, How and What’ of learning design enables us to drill down into the micro-aspects of teaching and identify the tiny changes we can make to effect a big difference.

The Marginal Learning Gains Method: Micro Action Research

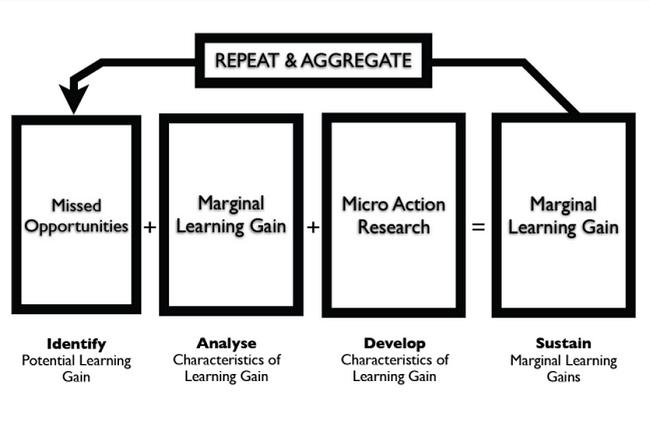

Whereas action research projects are designed to explore current practice within school and make a connection between external research and internal understanding of practice, ‘micro‘ action research takes even more of a surgical to current and everyday practice. Where Marginal Learning Gains is the theory, then micro-action research is the methodology. At the end of which, the Learning Gains can be pulled together (AGGREGATED) to ensure sustained impact on learning over time.

Once you have identified a Marginal Learning Gain that you want to develop, embed and sustain within your everyday practice, you simply identify another key component and apply the same process. That’s where the Aggregation of Marginal Learning Gains starts to really take a hold.

In micro action research, it’s all about specifics. You focus on way to develop just one aspect of pedagogy (the Marginal Learning Gain) with a specific group within a limited timeframe. It’s a very controlled, manageable method. Not only that, it doesn’t require you to do anything significantly different from what you already do. The main difference is in how you think and with this, how you observe the learning that takes place.

Posing a Marginal Learning Gains (Micro Action Research) Question

You may ask yourself (and others), ”How can I improve my teaching from ‘good’ to ‘outstanding’?” but feel constantly frustrated with this question because you are doing everything you know you should be doing.

Instead, applying Marginal Learning Gains Theory and using a process of micro action research enables you to reframe your question. In this way, you can systematically assess the impact of any specific changes you test out. So your question will sound more like this:

“How can I use...paired discussion [SPECIFIC STRATEGY]...so that there is an improvement in...the quality of learning talk [SPECIFIC STRATEGY] with...five Year 9 boys [FOCUS GROUP] over...three lessons [TIMEFRAME]”

The handy thing about this approach is that the research can be undertaken without making massive changes or requiring hours of pre-planning.

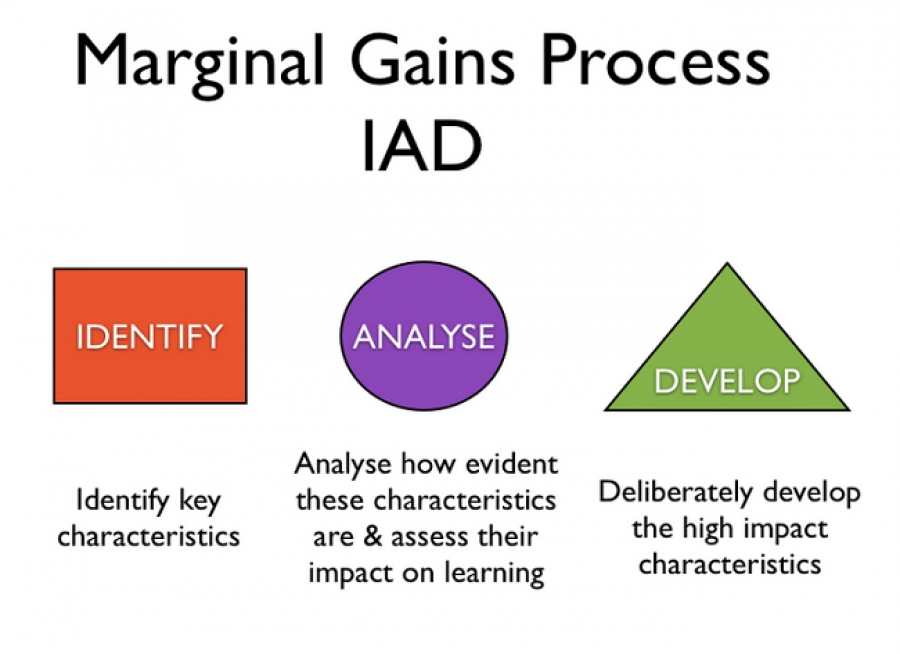

First, you IDENTIFY what your focus needs to be as a result of your micro action research question. Then, between the first and the second lesson, you ANALYSE the characteristics of what you expect to hear and see when you listen to ‘quality learning talk’. In the third and fourth lessons, you focus on DEVELOPING those specific characteristics through the small changes you implement. You are then in a position to SUSTAIN this approach in your everyday practice. If you then repeat the process with another marginal learning gain, the impact of changes can be aggregated to monitor overall improvements.

EXAMPLE 1: Marginal Learning Gain - ENGAGEMENT IN DISCUSSION

How do I ensure all learners actively participate and make contributions during group discussions?

IDENTIFY: You teach a student who is reluctant to offer answers, is painfully shy or simply lacks confidence to participate in discussions. You know what this student writes in their book, and they clearly understand difficult concepts and they are more than able to tackle high levels of challenge.

You recognise the benefit of them making contributions in class, for their own resilience and confidence, and for their peers to hear their great ideas, but you cannot get them to share and articulate their thoughts with others.

ANALYSE: Having discussed this with the student, it is clear that they lack the resilience to ‘dare to contribute’ during discussions for fear of making a mistake and getting it wrong. You decide that you need to focus on ways to make it feel safe for students to contribute and actively participate in discussions.

DEVELOP: On reflection, you note that often, when asking for pupils to give feedback after a discussion, you end up hearing from the person who has just done the majority of the talking. So you decide that by making a change to how you frame and illicit responses from groups during discusons is the Marginal Learning Gain you want to develop.

TEST: Without making any major changes in your lesson design, you simply adjust the way in which you set up a discussion activity in your next lesson:

Instead of asking pupils to discuss in pairs or small groups and then ask, “So what did you come up with...?”

Your Marginal Learning Gain project means that you reframe the discussion activity as follows:

“Discuss this in pairs and when you give feedback to the whole group, I’m going to ask you to tell me what you HEARD (not what you SAID).”

IMPACT: As a result of this reframing, the reluctant student has their ideas shared with the group but without any individual ‘spotlight’ pressure being placed on them. So the reluctant student gets to hear somebody else validating their ideas when they share them with the group and they also get a confidence-boost when their ideas are well received’ as well as possibly even impressing the rest of the group. At the same time, the group benefits from hearing the insight of one of their peers and you glean valuable assessment feedback that will inform the rest of the lesson. If you swap who you ask for the feedback, you may now ask the reluctant student to contribute, and they are offering what they have HEARD, and not their own ideas. By introducing this strategy as a regular part of your discussion technique, and regularly changing whom you ask for the feedback, it becomes clear that to the reluctant student that to contribute ideas is a safe thing to do.

The beauty of Marginal Learning Gains is that it begins with looking at what is already working well but could be even better but it is by no means a quick-fix approach. Instead, it is probably better to think of it as a form of microsurgery. It is all about looking very deeply into the smallest aspects of practice in order to secure, improve and develop them.

Marginal Learning Gains theory provides a really manageable starting point to design sustainable improvements. It is a great starting point for anybody who is either just embarking - or well on their way - to becoming a highly reflective practitioner. The approach of Marginal Learning Gains is to ensure that for every aspect of learning that we take the trouble, time and energy to design, we also take as much reflect upon these practices.

In this way, we get to squeeze as much learning as we possibly can out of a simple question-stem, everyday instruction, a card sort or an organisational strategy so it can be tweaked, adapted, developed and re-applied as highly effective aspects of practice.

EXAMPLE 2: Marginal Learning Gain - EXPECTATIONS

How do I communicate high aspirations for my learners in my lessons?

IDENTIFY: Every teacher is involved in the complex business of fostering high aspirations in our learners. Finding a practical way to do this through the learning that we design and how we deliver it can be incredibly challenging. It is true to say that to do so would constitute far more than a Marginal Learning Gain as if we are able to find a way to establish a highly aspirational culture in our lessons, then this has the potential to pervade whole-school culture. As always, striving for an aspirational culture, the Marginal Learning Gains can be found nestled deep inside what is meant by ‘aspiration’.

What is really worth focusing on is ‘expectations’. It’s a mindset thing. The Marginal Learning Gain here is found in the mindset of the teacher and how the expectations of the teacher are, however inadvertently, communicated through the design and delivery of lessons. It comes down to a (tiny) change in our language and, ultimately, a change in the language and mindset of our learners.

It is worth returning to the Marginal Gains guru at this point and thinking about how ‘hopeful’ Dave Brailsford was on the morning of the first leg of the 2012 Tour de France? And, as a result of the climate of high aspiration and expectation he had established, how ‘hopeful‘ was Bradley Wiggins on that first day?

Often, when planning lessons together, discussion will focus on ‘hoping’ that the students will get to the (x) task. Again, in post-lesson reflections, the discussion is often characterised by ‘hoping’ that the group would have achieved (x).

ANALYSE: A number of enquiry questions may with this particular Marginal Learning Gain and the final question here is a great one to hone in on as the Marginal Learning Gain opportunity.

• How do we establish a culture of aspirational learning through the language in which we think and speak?

• What practical strategies can we implement to establish a culture of aspirational

learning?

• How can we deliberately develop learner aspirations through our own mindset and

language?

• How will we know when it’s working?

• What language do I think in?

DEVELOP: When you are thinking about the lessons you are planning, rather than thinking in terms of ‘hope‘ the MLG comes when you start your lesson design, think in terms of what you expect. And with this, what you expect of individual students. One outcome of thinking and talking in highly aspirational ways, it that it you will start to avoid using the word ‘hope’ and with it, ‘might’ and ‘should’. By thinking and planning in terms of ‘What I expect students to achieve as a result of today’s lesson”, the lesson design is directly influenced by a concrete ambition for learners:

What do I hopestudents will be able to do as a result of this lesson?

BECOMES

What do I expectstudents to be able to do as a result of the lesson?

This then has a direct impact on learner mindset because when we then begin to ask learners to set their own goals (and expectations) ahead of the lesson, we can, using the same language, require them to frame their thinking and goal-setting in the language of expectations so that students agree / write / feedback:

1. “I expect to complete…”

2. “I expect to achieve….”

3. “I expect to be able to…”

In this way, learners are starting to really own their ambition. They select what goals they want to aim for and take responsibility for and ownership of these goals.

When the time comes to assess whether learners have achieved their goals and we ask them to reflect on their progress, we can ask them to use the same language as a prefix to stating what they actually achieved:

I expected to have completed / achieved / to be able to…and I did / didn’t quite /

didn’t…because…

SUSTAIN: A highly aspirational learning culture is characterised by frequent use of expectant language and is shared by teachers and learners alike. So when we think it first, we are more likely to use it in our learning outcomes, lesson design and conversations with learners. They, in turn, use the same language. They are specific in what they want to achieve, they set their own goals and they expect to achieve them. When they do achieve them, they are able to provide evidence for how this was done and If for some reason they do not achieve these goals, they are immediately prompted to ask why not and what steps they WILL take to meet their next goal.

By changing “I can” statements into “I will” statements, learners not only begin to ‘own’ their ambition but really commit to making it happen. For example, a tiny tweak to a plenary can become an expectation and commitment to future action:

“As a result of today’s lesson, I can….”

BECOMES

“As a result of today’s lesson, I will….”

And, as an addition:

“As a result of today’s lesson (intended learning outcome), I can (action / application of secure knowledge, understanding or skill)...so that I will (commitment to self-defined learning goal)…”

Moving from a hopeful to expectant teaching mindset has a direct impact on how we structure learning. If we expect certain things to happen, we need to be really clear about why, how and when this will happen. So when we pose questions or set up discussions, the following change occurs:

‘I hope they come up with some good responses’

BECOMES

‘I expect them to generate (insert number) high quality, well thought-out and considered

responses in (n) minutes’

In being explicit about expectations, we can frame success criteria in a far more purposeful and succinct way. If we want a group to come up with some good questions about a topic, we can start to think about (a) what constitutes a ‘good’ answer and (b) how many questions we realistically, or ambitiously, expect them to come up with. We can then specifically tell them how many questions we really expect them to generate. Unpicking EXPECTATIONS is just one example of the massive potential of using the Theory of Marginal Learning Gains to refine and develop quality learning experiences.

Benefits of applying the Theory of Marginal Learning Gains

• Applying the Theory of Marginal Learning Gains enables teachers to think deeply about the things that they know are already working well. This results in high levels of

engagement in professional development.

• Adopted as a whole-school approach Marginal Learning Gains Theory provides every teacher with the opportunity to hone in on very specific elements of their everyday practice and just focus on that, rather than try to improve everything, at all times.

• By creating limited time frames and focused micro-action research projects with groups of specific students, on-going development and innovation is manageable and can become integrated into everyday practice rather than an additional bolt-on for the enthusiastic few.

• Findings from micro-action research projects can be collated as they are completed throughout the year. They can then be frequently shared as ‘study-pieces’ all year, contributing to a culture

f professional learning dialogue between all staff and informing timely interventions as-and-when they are needed, rather than waiting for all findings to be published in one document as part of an annual report.

• Innovation and development becomes part of the everyday offer of teaching and learning on-going process and as such, part of the fabric of the school.

• Collating the micro-action research projects into a summary study (Aggregation) provides an fantastic opportunity for a summative event of a staff-led sharing effective practice event which can then enable a detailed analysis of patterns and important outcomes.

• Marginal Learning Gains Theory can be integrated into an on-going coaching programme to give coaching conversations a sharper focus on pedagogy on aspects of teaching and learning that can be developed as part of everyday practice. This means that the ‘gains’ can be purposefully and deliberately made for the students who are in front of us now. Not as a ‘quick-fix’, but as an iterative process of innovation and development.

To learn more about Marginal Learning Gains Theory, visit www.marginallearninggains.com.