Luckily, despite the seemingly irrelevant nature of learning about Steinbeck, Shakespeare and Bronte, literature is rich in cross curricular skills that are useful far beyond their examination. Analysis, exploration and creative insight are all skills tested on the exam but they are also skills that contribute to forming critical, interesting and cultured citizens of our world. These are not easy skills to teach let alone convince children to learn; however, convincing this boisterous class of the merit in learning such skills has led to many of them racing past average and consistently delivering outstanding thinking.

Story Telling

What a magically powerful tool a story can be in the hands of a teacher. This class love a good story. Lessons always begin with a story linked to the ‘why’ of our learning outcome and involving my time machine. Picking out individuals, I show them each their futures as a result of the learning that will take place in the lesson ahead. If I cannot think of a reason for what I am teaching, it does not get taught. The future holds fashion savvy footballers (linked to character appearance); cultured lads about town (linked to sophistication in register) and winning moments in job interviews (linked to the common ground of literature being part of everyone’s culture). The lesson starts with an inspiring sparkle, making connections that they may not have made themselves between their learning and their futures. They can see that what I am about to teach them has substance and purpose and they are ready to give brain power to the hard work ahead.

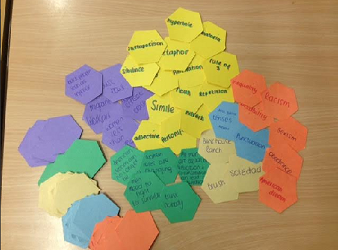

Convinced of its merit, pupils are each given six sets of different coloured hexagons to begin their analytical training. Each individual colour represents something that the examiner wants to see in an extended response: language, structure, themes, writer’s ideas, context and setting. Pupils write uni structural points, based on their current knowledge, onto each of their hexagons.Pupils are used to the terms used for SOLO levels and so understand that each hexagon must have an individual statement written on. If you have never heard of uni structural before, it might be good to start back at this post: SOLO for Beginners before continuing.

Each analytical tool created is personal to the individual that made it. If pupils don’t understand a term or an idea (yet) then they leave it out until they do. One pupil having a juxtaposition hexagon while another only has simple similes and word classes, means the tool is differentiated for me. Seeing clearly what pupils are already confident with allows me to focus on what pupils do not yet know in subsequent lessons. Making the tool gives them ownership over their current knowledge, using the tool shows them how to use this knowledge to analyse in greater depth.

To begin, pupils read a small section of the novel with a view to exploring the author’s intentions. Beginning with the language hexagons, they identify the language and techniques used within the extract. As they read, they simply pull across any hexagons naming language devices or word types used by the author making a pile of yellow hexagons.

Once they find out what the writer used, they then look again to see if the language has any relevance to the context by pulling across the context hexagons and linking them to the language use. This continues with all other hexagons until they have a pile of multi coloured hexagons that all have relevance to the extract. Taking pupils through the SOLO levels in this way highlights the importance of a strong base knowledge. The more they know, they more they can find within the extract. Their pile of multi structural hexagons now represents their investigation. They have, like detectives, looked at the many elements that have gone into the creation of this extract.

However, this is now a multi-structural pile of hexagons. They have analysed in theory but this is not an extended response…yet.

Relational Responses

Pupils can now use the hexagons to create a chain of thinking. They have identified the writer’s language choices in relation to themes, ideas, context, structure and setting; they must now question the writer’s intentions by using their findings. For example, “The way a bear drags his paws.” The writer uses a simile to describe Lennie. Why? Linking to the context, he may have been representing how migrant workers were dehumanised as a result of the economic downturn. Why? This links with the theme of disability as Lennie is disabled in the story but could represent the disability of all migrant workers. Why? The writer wants to show that in a world this cruel, only the strong can survive. Pupils are using the hexagons to create an analytical chain of thinking. The hexagons are laid out in their chosen order and create the basis for their written response.

This process of exploration and reorganisation is not easy. Pupils get stuck; they get frustrated; they ask each other for help; they pull angry faces; much ‘banter for learning’ takes place. Pupils look to me for reassurance; I don’t give them the answers but question them further, modelling questioning and getting them thinking in the right direction. This work requires some serious thinking and determination to succeed. The pupils may be challenging but this lesson gives them a challenge that they enjoy achieving in. The challenge has merit beyond the terminal examination and they understand that analysis is a useful tool for life not just literature. Despite initially seeming irrelevant, learning about a dead American and his work has supported pupils in forming critical opinions and developing interesting explorations and insights into his purpose. They understand what analysis is and can recreate the process when the hexagons are taken away as well as being able to apply the process in different contexts. Best of all, I don’t need excuses for their results as they have moved from producing average D/C responses up to analytical, insightful B/A grades.

Do you use solo taxonomy or hexagons in lessons? If so, tell us about it in the comments section below!