Every year I make the attempt to alter my voice to become characters in stories that I read to the class. Every year I try to set the tone for our reading with pictures, lights, and sounds. Every year I some how fall short. I either forget the dialect I originally used, I play the wrong kind of music in the background, or I’m honestly just having an off day.

How does a student gain knowledge? Is it via reading, or rather by collaborative exercises? As an international educator of 25 years and currently teaching in Mumbai, Maggie Hos-McGrane gives her thoughts on the issue.

I'm reading George Siemens' Knowing Knowledge very slowly as there is a lot to take in and think about. There are a couple of questions that I'm thinking about today:

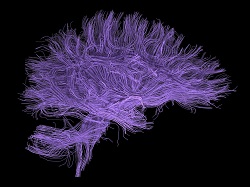

I'm now thinking about the connection between learning and knowing, and have come across the word connectivism which asserts that learning is a network-forming process. The success of these networks in encouraging knowledge varies depending on a variety of things:

Given how fast the UK’s teaching communities are growing in multiple directions, different ideals of education are constantly emerging. Are the lesson plans of old being pushed out for a new, more entertaining way of teaching? The Perfect Ofsted English lesson author David Didau discusses this.

First of all I need to come clean. Up until pretty recently I was a fully paid up member of the Cult of Outstanding™. Last January I considered myself to be a teacher at the height of my powers. In the spirit of self-congratulation I posted a blog entitled Anatomy of an Outstanding Lesson in which I detailed a lesson which I confidently supposed was the apotheosis of great teaching, and stood back to receive plaudits. And indeed they were forthcoming. I was roundly congratulated and felt myself extraordinarily clever.

First of all I need to come clean. Up until pretty recently I was a fully paid up member of the Cult of Outstanding™. Last January I considered myself to be a teacher at the height of my powers. In the spirit of self-congratulation I posted a blog entitled Anatomy of an Outstanding Lesson in which I detailed a lesson which I confidently supposed was the apotheosis of great teaching, and stood back to receive plaudits. And indeed they were forthcoming. I was roundly congratulated and felt myself extraordinarily clever.

And then Cristina Milos got in touch to tell me that there was no such thing as an outstanding lesson. I was, she patiently pointed out, deluding myself. When I sputtered my objections she directed me to a video of Robert Bjork explaining the need to dissociate learning from performance. Now no one enjoys being told they’re a fool, but I have to say that I’m profoundly grateful to Cristina for not pulling her punches; nothing else has had anywhere near the impact on my thinking about teaching and learning. When you start thinking in this way, it becomes increasingly obvious just how little we know and understand about what we do.

Photo credit: Louis Shackleton

Five years ago, when I first started working with clients on social media, I needed to explain to many of them what it was. Times have changed. Nearly every school now has some kind of presence on social media, but few use it well.

In a nutshell, social media is where your entire school community resides:

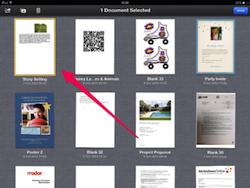

Pupils at South Cave CE Primary School have been collaborating on descriptive writing activities with teacher Mr Tatton. The classroom has no wi-fi connectivity. Each pupil had an iPad mini and used the new Airdrop feature in iOS 7 to share work with each other and to send finished content to the teacher's iPad for display.

The teacher shared a Pages document with each pupil's iPad using Airdrop. The pupils were able to open the document and followed the prompt, which was to select an image and begin to imagine and describe what it might like to be there. The pupils then shared their work with an agreed partner who provided feedback and improvements before the work was presented to the class in the form of a Tellagami animation.

Tried and tested, and proving incredibly successful, these simple ways of integrating iPads into a lesson helps to keep pupils focused, organised, and engaged with their learning. These tips could be used in any lesson with any year group, but I will share examples of contemporary best practice from my role as Upper Key Stage 2 teacher and ICT Coordinator. A teacher does not even need a whole class set of iPads to be able to replicate these methods; one, six, or eight devices will also work well.

A great way of controlling both the physical storing, charging and distribution of a set of mobile devices, and also to assist the smooth running of iPad lessons, is by allocating the role of ‘Digital Leader’ to a small group of pupils within your class. Digital Leaders are students who are enthusiastic about technology and are able to share examples of best practice and model correct behaviour to their peers, supporting teachers and increasing the potential of ICT in the school. They can be trained to conduct a wide variety of weekly jobs, such as deleting photographs on the iPad camera roll, and can support other pupils and teachers when needed, perhaps when using a new website or App, or updating the class wiki or blog.

SOLO evangelist Lisa Ashes has a new method for students to observe their progress in lessons. Using her Year 12 English class as an example, she asks 3 questions to each pupil, who after reviewing their answers, appreciate how deeper methods of exploration help them acquire a different perspective and achieve a higher level of understanding.

The way that I create a meta cognitive wrapper is by carefully creating three questions that will start and end my lesson; the questions link directly to my learning outcomes.

The first question is about the current knowledge and understanding of the student. The second should embody the type of SOLO thinking; research, analysis, evaluation and/or creation of new ideas.

My final question asks pupils to think about the processes they are about to undertake, to prove they have learnt something.

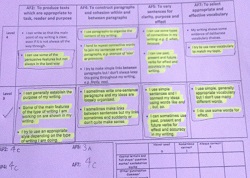

Having students identify for themselves where they think they need to improve and then comparing this to their performance on a task will give an accurate insight into which parts of the criteria they do not understand how to satisfy. The teacher can then point this out and explain how it can be achieved. A good method to conduct this is by using 'predictive grids':

Too often, students see the grade that they receive and do not take enough notice into the written feedback that is given during marking. Dylan Wiliam's suggestion of not giving the grade to the students works but I've been wanting the students to engage with the success criteria when it comes to their exams and they really are incredibly motivated by seeing the grades, or even a number.

Something suggested by a colleague, which I've started to implement with exam classes, is 'predictive grids'. These are success criteria grids (usually using the exam board language as much as possible) which the students highlight according to what they think they achieved in the piece of work. This can either be done directly after the piece of work is finished or the lesson after which is what I usually prefer to do. When the work is marked, the teacher can then see where specifically the students are not achieving, but also see if the students know if they are not achieving in that particular area.

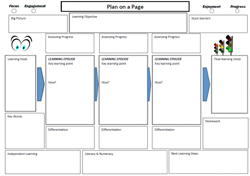

If you are involved in education and use twitter you can’t not have seen Ross McGill’s excellent 5 Minute Lesson Plan. A great resource that supports teachers with planning effective lessons, in 5 minutes or less.

This inspired us to produce a ‘Plan on a Page’, based on the great principles of the 5 minute plan:

At the moment we are trialling it in school, but it looks like this:

As the end of the half term break draws nigh, I’m left thinking about the return to school and all that this entails. My mind buzzes with lesson planning, resource-creating, teaching, assemblies; duties, students, teachers, parents, paperwork, meetings; the highs, the lows, the drama and the laughter… The list is endless.

The familiar shift from off-duty to switched-on has begun. Through this heavy mist of the things to plan before the term starts, poses one particular question to me, as clear as crystal as ice-water; the word ‘why’.

This word is the one thing that really stays in focus for me through all my preparations. Whether I am lesson planning or organising meetings, it won’t leave me. The question hovers overhead, smiling knowingly and nodding. If the answer to that question makes you happy, then I guess you are one with the world, even on difficult days. I question ‘why’ most of the time, because it keeps me in check; it keeps me focused and relights my passion on the darkest days; I want this to be the case for my students also.

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom