Most teachers will say that they are creative every day, citing how they respond to the dynamics of groups and situations which arise. However, it is good to have a reminder about the deliberate use of strategies to promote creative teaching / learning; refreshing our memories, or even meeting new options to give a creative boost to our classroom. Here are five you can use right away:

1. Creative peer feedback

When visiting a school in the Scottish Highlands, I was really impressed with a feedback hot-seating activity.

The pupils had created their own Success Criteria for designing a den, after a morning of intensive work they were asked to form a group to do their hot seating. A pupil volunteered to show their work first; the rest of the group then offered comments and questions linked to the Success Criteria, based on Tickled Pink (good features) and Green for Growth (points to develop). They were able to ask open questions like “Can you explain why you would choose to use the materials in that way?”

The pupils were really engaged in the process and took complete ownership of it giving a greater depth of dialogue and thinking to peer feedback.

Class 5W have been hot seating as Ben and Ray from "Where the Poppies Now Grow" @Martin_Impey #StGerardsPSHE #StGerardsEnglish pic.twitter.com/wlhy5rfKUm

— St. Gerard's (@StGerardsWidnes) November 6, 2017

A dramatic inquiry-based approach to learning, this is a great way to immerse children in the classroom experience. The teacher plans the fictional context with tasks and activities to complete, enabling them to gain a deeper understanding and experience of the topic. Pupils are cast as experts in working for a client on a commission, and complete a variety of activities, such as pupils becoming a CSI team to solve the murder of Thomas Becket.

I have seen this used in a wide range of contexts, from a class taking on the design of a National Heritage site for a local attraction with Year 7, to helping the United Nations to solve the Syrian Crisis with Sixth Formers. This Dorothy Heathcote-invented strategy is a powerful medium in the classroom. Find out more at: www.mantleoftheexpert.com

All set for a very special delivery from our client @DragonsofWales for our Mantle of the Expert. The children will become experts at caring for and raising a baby dragon. #primaryrocks pic.twitter.com/5oG43Khhf0

— Teacher Glitter (@Teacherglitter) August 9, 2018

Show your class a TED Talk on a topic which they can relate to. This stimulates curiosity and puts them in the Learning Pit (www.jamesnottingham.co.uk/learning-pit), ideal given that cognitive conflict is key to engagement. Work with the pupils to create the success criteria for an attention-grabbing TED talk. This will guide their work and give the opportunity to self or peer assess.

To support Growth Mindset, employ the concept of The Learning Pit into the classroom. #edchat #educhat @MindShiftKQED pic.twitter.com/wANvNnxhwa

— Michael Manton (@mmanton1) October 25, 2017

The pupils then get the opportunity to research and prepare their own presentation. Build in some drafting and peer feedback to produce the best possible piece of work; ask their partner to review the work using the criteria; give two stars and a wish to improve the work.

The next stage is time for the pupils to work to redraft and improve. Then they need to practise the delivery of the talk - keep it timed to help them. Giving an opportunity to try out their talk with their partner offers another opportunity to improve the work and model the ongoing learning process. You then need to give a sharing opportunity to reduce the number of competitors to five. This way, you can ask a ‘celebrity judge’ to come in, listen to the talks, and give feedback. Find out more at: https://www.ted.com/talks.

4. Gold fishing

One of my all-time favourites, this encourages a diverse range of contributions to a whole-class discussion. Split your class in half. Group A gets one argument to prepare from a set of resources; this contrasts with Group B, who get the opposing argument and resources. This works well with historical debates like “Field Marshal Haig deserved his title of Butcher of the Somme”.

The two groups get a set amount of time to prepare five key points, which will enable them to talk for two minutes (use a timing which is age-appropriate - this was for Year 9). Once they have had the preparation time, arrange two concentric circles of chairs in your classroom: the inner circle facing towards your classroom walls, the outer circle facing in.

Group A sit on the inner circle chairs, while Group B then sit on the outer circle chairs so that they are in pairs sitting opposite each other. Group A then have two minutes to talk and convince their partner that they have the ‘best’ argument. Group B must listen only. Group B then gets their two minutes to convince the A partner that they have the best argument. I then get the B group to move two chairs clockwise and repeat the process. This is repeated twice more. The pupils then must switch arguments using the same talk protocol. This time they get feedback from their partner on what they many have missed. This will be a very noisy section of the lesson.

I then ask the pupils to return the furniture to the original format and take their seats. The next step is to reflect on why I may have chosen this activity - they will come up with the need to listen effectively, developing their views and reasoning. They are then fully prepared to debate the questions as a class, and write up their judgement with quality reasoning.

5. Get your perspective specs on!

When working with pupils to get a deeper understanding of different historical viewpoints, these can be a great tool. Get your pupils to design and make some ‘perspective specs’ - genuinely outrageous glasses. Then model the process with them, looking at a source like Henry VIII’s court spending. Ask them to consider what it tells them about Henry VII and his style of government? Then, in pairs, put the specs on. Half the class are to be Henry VII, the other half Henry VIII. How would they view the source differently or the same?

The physical act of putting the specs on helps pupils to understand that perspective and interpretations of the same piece of evidence can be very different. This time to explore ideas in their pairs will give them confidence in feeding back ideas as a bigger group. I usually record their views in two columns on the board to gain a collaborative class view on perspective.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Both cars can go 124 mph. One can get there in 7.2 seconds. And the other, if it’s lucky, can do it in 12 seconds - provided the duct tape holds. That’s pretty much the only difference between my 1991 740 Volvo station wagon and a Porsche 918 Spyder. Well, that and the Porsche only has one cup holder.

We all know our students can achieve this 124 mph level of creativity (call it Csikszentmihalyi’s “flow”), but for some it takes a while to get there. One way to speed up the process is using Project Based Learning (PBL). PBL accelerates creativity through sufficiently structuring learning goals and requirements while allowing students to choose between differentiated options. This dual-axle approach then provides students with the necessary framework to be creative in ways that are meaningful to them and purposeful to the project. Here’s your very own PBL test drive (or tune-up, if you’ve already taken it out for a spin) along with a few common repairs and turbochargers.

Axle I: Structuring learning goals and requirements

Many teachers (including myself, when I began) wrongfully believe that the quickest route to creative thinking is a blank sheet of paper. While that may be the case for some, in order for most to get comfortable in the driver’s seat, we need to slow down and show them a map so they know where they’re headed first. Your map needs:

Purpose: Using projects as formative and/or summative assessments is a fantastic alternative to tests, because they allow students to complete work in steps and reflect on the process.

Pro tip: Have students explain why they are doing a project this unit instead of taking a test, and what the advantages are.

Direction: Essential questions activate student learning. The unit is called “reptiles,” but what are we talking about? Anatomy? What reptiles eat? Are we becoming reptiles? Preview the chapter to pique student interest: “What would happen if there were no reptiles?”

Pro tip: Don’t use a yes or no question or a question with a simple, short answer.

Model steps & provide examples: Before beginning each step, gather all students into “storytime” seating (everyone sitting close together in front of the projector). All students read the steps, you clarify, and have one student actually complete the steps in front of the class. In addition, provide digital instructions with an exemplar student example or make an example yourself.

Pro tip: If you have a student who misbehaves, let them show the perfect “wrong” example, then ask the class what was done wrong and how to correct it. This reinforces the correct procedure, and gives the student both a leadership role and positive attention.

Mini classes (<10 min): Students may need information given through a lecture, or may need a new technology tool explained to them. If flipped lessons or rotation stations are not possible, mini-classes definitely are. Reduce the lecture to the least amount of information possible, gather students in “storytime” seating, and rely heavily on checks for understanding to see what still needs to be explained.

Pro tip: If more time is needed, let students work on the project with what they learned during the first mini class for a bit before lecturing again.

Scope: Take the time in your requirements to think through what specifically you need to see in order to know that students have mastered the learning objectives. This is perhaps the second most important piece for accelerating creativity from the teacher’s perspective.

Pro tip: Don’t add tedious requirements that you aren’t going to enforce anyway (eg “use 4 colours on the title page,” “have exactly 8 examples of ‘ar verbs.’).

Rubric: This is the most important element. Including a rubric when the project is explained (not as it is turned in) lets students know where to focus their energy. The rubric becomes even more useful if a teacher walks through several example projects with their rubric scores.

Pro tip: See if there is already a proven, standardised rubric for what you are grading. And before adding vague statements like “very creative,” “creative,” “somewhat creative,” imagine explaining this to a student’s parents. Are you clear on what the differences are yourself? Make sure your students are too and give them examples. Does “creativity” even need to be a criterion? Hint: probably not.

Axle II. choose between differentiated options

Now that students have a map, let them choose the route. What you see as scenic, others see as long. Some like curves, others like straightaways. You will notice increased student interest right away, especially if your course was previously linear. You may wish to let students choose all of the options themselves or to choose some for them. Options can include:

What/how students learn: Let’s say the project involves explaining the main idea in Animal Farm through authoring the neighbouring city’s weekly newspaper. By giving students a placement test, the teacher might realise some students have already read the novel and assign those students a different book covering the same topic; why make students read the same book again if they can already convey the main idea?

Maybe a student with a learning difference has an accommodation to listen to the audiobook. If one of the requirements is to summarise each page in the margin, maybe this student creates a podcast based on every five minutes of the audiobook. Perhaps this then becomes an option for all students as well.

What students do: In a mixed-ability classroom, students can complete the same project but have different requirements. For example, if the activity for Spanish students is to design a menu and include full sentences with ser, estar, and three adjectives, high-achieving students could have the additional requirement of adding a biography of the chef that includes the preterite and imperfect.

How the student does it (story, worksheet, video, interview): Perhaps the overall goal of your project is to compare and contrast the history, culture and government of two countries. Allowing students to choose how they do this project might result in an infographic, a mock UN debate between the two countries, interviewing citizens (whether real or classmates) from the countries who describe the issues, or making a slide deck.

The result: purposeful & meaningful creativity

Now that students have a map and have chosen their route, get out of the way while they open the throttle. Let them work during class if possible, or at least work on each step for 10-15 minutes during class to troubleshoot with each other and check in with you. This is your time to ensure everyone successfully crosses the finish line. If a student isn’t on track, maybe it’s time to help them select a different option. You can also prevent overheating (creativity being used where not purposeful to the project - eg spending 20+ minutes on the title page).

Pro tip: Don’t waste time rotating to see if students are complying with the instructions to work. Engage with students. Constantly be checking-off where each student is in the work process.

Hot Rod Examples

|

Hot Rods |

|

|

Student & Sample |

Description |

|

Gillian M.

|

Find out where gum originated, the science behind it, and its health effects in this video! Project description: Make a five-minute video about something that interests you.

|

|

Clara M.

|

What is yodelling? Find out about its history and learn how to yodel in Spanish with this video. Project description: Five-to-seven minute student videos in Spanish modelling how to be curious for viewers of Sesame Street.

|

|

Michael Alvarenga, Shruti Sridhar Por el Mismo Sueño (pdf)

|

Bilingual narratives and superhero comics of day labourers describing their family histories, culture and daily lives. 100% written and edited by students. Project description: Demonstrate that you are an upstanding citizen through advocating on behalf of a Spanish-speaking community, using the skills you have improved through taking this class.

|

Repairs

Feel like you’re already doing this, but it’s not working? Let’s check under the hood. Maybe you have a loose gasket that’s holding students back.

Taking points off for late work: Are you taking off 10% for each day something is late? Here’s what can happen when you give your students extra time to work on a project they are passionate about. Hot Rod Clara M’s PBL YouTube video was supposed to be 3-5 minutes long. After asking for an extension, her final video was 10 minutes long. It has over 100,000 views!

Giving 0’s for incomplete work: Let’s say a student hasn’t completed his solar system PBL assignment either because he was absent, he didn’t understand the assignment, or he was playing FortNite. Giving him a zero (or hopefully a 50, if you have a 50% floor) lets him off the hook. It signals that you and he are moving on from this assignment and that it is acceptable to not master all of the curriculum in class.

Pro tip: Replace this with an “incomplete.” Explain that it is not possible to measure the student’s mastery of the learning goals for this unit, or for class, until the project is done.

Not letting students shift out of 1st gear: “Be as creative as you want... Using PowerPoint 2003!” No! Just because that’s what you know, doesn’t mean students should be stuck with this option. Let your students surprise and delight you. Explain the requirements (Axle I), offer them options (Axle II), and get out of the way. If a student is a Prezi expert or wants to learn how to use Adobe Spark, let them! They will be that much more motivated when applying creativity to your material.

Turbocharger (warning: may void warranty)

So you’re a PBL pro looking for some extra tips. Your Porsche 918 Spyder is running just fine, thank you. Here are a few creativity turbochargers.

Design thinking: What every method of brainstorming wants to be when it grows up. This will help your students come up with dozens of ideas, instead of three or four. If it’s good enough for Stanford’s d.School, it’s good enough for me.

Makerspace: Before class starts, bring in art supplies. Let students colour, create with pipe cleaners, cut things out; let them know today will be different from other days.

The Tuning Protocol: This unique method of peer feedback will change how you have students comment on each other's work in progress forever.

Time:

Time to get on the road and take PBL out for a spin! You have the basics, and your students will welcome the learner-centred change from the “sage on the stage.”

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Another school year is upon us, with GCSE season a recent memory: a period in the school calendar that, as ever, brought stress, anxiety and a lot of prayers. Year on year, the same patterns emerge in a relentless bid to ensure that the pupils are the best that they can be, leaving schools in ‘stuck record’ syndrome.

You can picture the scene: frantic teachers throw everything possible at pupils through endless interventions, worksheets and helpful strategies whilst the nonchalant pupils happily coast lackadaisically before reality sets in, leading to late night cramming sessions. But it’s all worth it, as we see Year 11 pupils enjoying their summer and teachers enjoying the extra time to catch up on the piles of work forgotten in the past month. The late nights, the arguments and the tears (mainly from the teachers) are forgotten, and we subconsciously prepare to do it all over again.

And yet, what is the real toll? Everyone is exhausted and, although, cramming may lead to a short-term gain, it leaves pupils less prepared for college and beyond. Pretty much, cram means can’t retain and master. Every year we think something has got to change to support the sanity of pupils and teachers, but the short-term pain becomes lost when pupils show a glimmer of success and progress, making it seem worthwhile.

So, the cycle continues, the GCSE season is back and all the reflection and “never again” resolutions quickly evaporate. It’s like having Dead or Alive’s cult hit You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) playing in the background. But we can change the tune by not waiting until next year to cram, but by starting right now, with revision utilising the spacing effect.

“The spacing effect is one of the oldest and best-documented phenomena in the history of learning and memory research.” (Bahrick & Hall, 2005)

Numerous studies provide evidence to suggest that spacing learning out has a greater impact in learning than massed study. More so, spaced repetition improves a person’s ability to retrieve information from memory.

Our current method of cramming during GCSE season may appear to have a short-term impact but learning from those sessions won’t stick. Instead, a steady, regular approach over time is necessary to improve learning and retention. Therefore, pupils who start preparing for next year’s GCSE now not only improve their results, but will be able to carry their learning with them to the next phase of their schooling or work life.

A classic study by Ebbinghaus suggests that new learning quickly erodes nearly 70% after one day and is nearly forgotten after one month. Unfortunately, knowing this probably does little to alleviate the frustration we have sometimes when pupils’ primary response in the next lesson is “I don’t remember!” But what it does demonstrate is that teaching without revisiting material will only lead to panicked, last-minute anxiety and cramming when the month of May approaches.

Here are three (of many) practical ways to embed the spacing effect in the classroom:

1. Use of low-stakes formative assessment strategies, such as quizzing, to regularly test key concepts spaced throughout the year.

2. Develop subject level revision mapping to ensure key concepts and topics are interleaved to support pupil home learning.

3. Find opportunities to revisit prior learning by making explicit links with new learning.

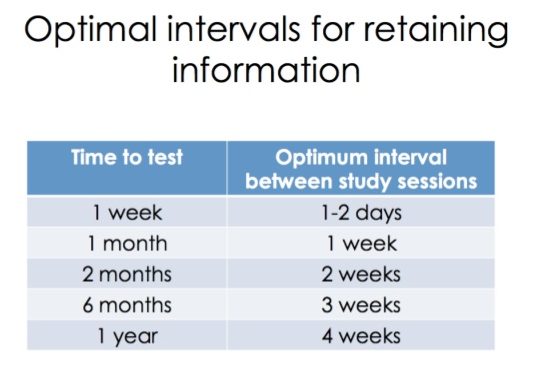

There are many ideas when it comes to when and how often to put the spacing effect into practice. However, Cepeda et al (2008) provide a helpful recommendation on the optimal intervals to maximise the potential of the spacing effect.

It may be hard to digest that, to learn, we must be on the verge of forgetting. However, it is time we changed our thinking. Helping pupils to stop cramming will always be difficult, but we can help by considering the spacing effect in our curriculum planning. Even more, we must improve pupils’ revision skills so that they know when and how to study.

Cramming may work in the short term, but for learning to last steady, regular, spaced learning needs to take place. The impact of the spacing effect is more than improving pupil attainment; it will also help pupils’ learning to stick.

References

Bahrick, H.P. & Hall, L.K. (2005). The importance of retrieval failures to long-term retention: A metacognitive explanation of the spacing effect. Journal of Memory and Language, 52, 566-577.

Cepeda, N.J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J.T. & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning: A temporary ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological Science, 19, 1095-1102.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

‘Innovation’ is an interesting word to me; not just because I’m ‘innovation lead’ at Aureus School, but because I think it is a word which (in education) seems to carry many preconceived images. If I say to you “Oh they’re an innovative teacher”, all too often the perception seems to be of a teacher who’s at home using the latest technology, whose classroom is awash with the latest teaching trends, and who leads CPD on “how to use your interactive whiteboard more effectively”.

This article on innovation covers none of that! I’m not dismissing edtech nor the associated innovations therein, but I am going to talk about the innovator's mindset.

The innovator's mindset is the true way every teacher can innovate in any setting! As I see it, said mindset comprises of four component parts:

If you can adopt the innovator’s mindset (and truly anyone can) you can make this academic year, and in fact every academic year, one in which you innovate in a meaningful way!

1. Review

This is about you the teacher, the subject specialist, and the pedagogical perfectionist. Take a moment or two to review your last academic year or even the last few. I suggest reviewing on two fronts:

Your subject. The content you’ve taught, the way it was received, and the impact it had. Make note of what went well, and what you think you could improve.

Your pedagogy. Review the way you taught your subject. Did you deliver content in a variety of ways? Did you adapt work for learners who were struggling? How good was your differentiation? Did you really stretch and challenge all your students? As part of this review, take to the internet and the educational bookstores, choose something on which you’d like to read up and refresh your knowledge. For example, spend an hour or so reading up on stretch and challenge ideas, and make some notes on things you could try to freshen up content you deliver in the new term.

2. Do

Teach. Get into your class and teach your stuff using the ideas you have read about. Adapt your technique based on both what worked last year and what could have been done better. Invite others into your class to watch you! Ask others if you can observe them teaching too.

3. Review

This time, don’t wait til the end of the academic year to review what is working in your class and what can be refined. My suggestion to support your most innovative year is that you make time in the first weekend of every half term break to pause and review what is going well, what can be done better, and choose a topic to brush up on. Look again at your subject and your pedagogy. Think about what you did in your classroom, what discussions you had with those who have observed you and what you’ve seen in others.

If you read up on stretch and challenge six weeks ago, then choose questioning this time and spend an hour reading up on ideas to better question in your classroom. Use these to develop new strategies that will help you deliver your content in the next term.

4. Re-do

Get back into your classroom with refined focus, content ready to be taught using techniques you have reviewed yourself and with colleagues, and perspective on your pedagogy you’ve refreshed.

It really is as easy as those four steps to keep your mindset innovative throughout an academic year!

...and 5! Sharing what you do to keep you on the innovative path

One extra tip to keep yourself innovating: Share! Sharing what you are doing with others is a great way to keep your mindset innovative! Consider creating your own blog, or even a shared blog with colleagues who agree to share your innovator's mindset this year. At the end of each half term, take it in turns to post about your term, what has gone well, what you’re considering changing, and what areas of your pedagogy you are reading up on. Innovation does not happen inside a bubble. Real innovation happens when you look outside yourself, your organisation, and even your sector to draw in inspiration for afar. To do this well you have to be sharing what you do.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Exploring student futures is imperative to developing a successful education system. It is a crucial part of answering the question: “What is education for?” - a question which, against all reason, often seems to get neglected. This is bewildering to me; after all, how can there be a hope of providing quality education to children and young people without being very clear on the end goal? This is akin to asking Usain Bolt to compete in a sprint race, without giving him an indication of the finish line or the time he is expected to complete it in.

If you are reading this, you are no doubt privy to the expectations heaped on teachers and school leaders about the importance of feedback in driving student success. If you hear the word “feedback”, and are haunted by images of lengthy, scribed comments that go ignored, much to your distress (how many hours of your life that you won’t get back?) and to the student’s peril, you are not alone.

“Teachers warn learning through play can lead to pupil disruption” was the title of an article printed by a Scottish newspaper in January this year. The article cited a recent report which had shown that some teachers in Scotland were worried about increasingly poor behaviour within classrooms when engaging in active learning.

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom