Your own continuing professional development (CPD) is absolutely vital to you as a teacher. Working in education is not a job that you just turn up and ‘do’: with ever-changing examination specifications, curriculum re-mapping and emerging research that causes us to revisit the way in which we teach, you cannot afford to disregard the importance of self-investment.

But training costs, right? Wrong! Granted, the squeeze on budgets grows tighter by the year, and schools often look to larger organisations to host or run their INSET, but this often has a whole-school focus, which may not always completely match up to or accommodate for your own professional development goals. However, there are a range of time-effective approaches that you can use to direct your own professional development this year.

Read for impact

I aim to read a small number of books with an educational focus each year, and this number has lessened with each year that I teach. I also look back and feel that perhaps a great deal of what I have read was simply wasted time. Why? I was not as focused, and I didn’t embed certain ideals or concepts within my own teaching as a result. In addition, some of the books that I picked up were perhaps not relevant to my role at the time. For instance, reading a book about leadership may be interesting at best, but if leadership is not an area that I want to pursue in the near future, is that the best way to spend my time?

Meek's take on reading is fascinating. Would be brilliant to collate a list of books based upon narrative experimentation for this alone: pic.twitter.com/aVr5LEpcvD

— Kat Howard (@SaysMiss) February 15, 2017

Now, I try to use two strategies when selecting reading for professional development: What is the focus? How will I use it? Read with a specific aspect of your teaching that you want to improve upon in mind or become more informed towards. Consequently, consider the practical ways that you will implement what you have read. This doesn’t need to be a monumental change; it may simply be a resource created that uses a particular model. Evidenced-based teaching need not be a laborious piece of action research, but can just take the shape of trying something out then reflecting upon it afterwards. You will find that you have made the purpose of your reading meaningful, additionally weighing up how effective it is on a day-to-day basis within your practice.

A summary of how I have use evidenced based teaching to streamline my practice and #ReduceMyWorkload #TENC18 #teamenglish pic.twitter.com/Yt1KoJq6AI

— Kat Howard (@SaysMiss) July 14, 2018

Look local

When seeking out ways to improve as an English teacher, particularly when it comes to subject knowledge, I have found a secret treasure-trove of outlets locally to assist me. From visiting National Trust properties for contextual knowledge, to public lectures at local universities to broaden my authorial understanding, there are a range of ways to grow your learning bank without straying far from home or attending a large, costly conference.

Out walking dusk today! @nationaltrust #teacher5aday pic.twitter.com/M6iPm7NX2P

— Kat Howard (@SaysMiss) December 27, 2016

Over and above that, setting up visits to local schools is a fantastic approach to specific CPD that will reap reward in both budget and time; in my experience, the professional discussions and relationships that evolve from such visits are so valuable. You may go with a particular focus related to the professional goals outlined by yourself at the start of the year, and walk away with so much more than that, with someone at the end of an email for guidance and support to boot.

Build a network

Working as a teacher lends itself easily to working in isolation: losing your days to planning, teaching and marking, with the interactions with colleagues being brief greetings in the corridor or directed meetings that have a specific agenda. However, collaboration is key to successful to personal progression, and if you have a particular goal in mind for the year ahead, share it with those around you. This will act as a starting point to exploring if others would like to team up in working on a project or research over the year ahead.

Collaboration will save the teaching profession! More here ⬇️ https://t.co/FIiqNlu3JK

— Kat Howard (@SaysMiss) July 20, 2018

For example, as an English teacher, I enjoy connecting with Maths or ICT teachers when piloting a new idea; usually because their skills are useful, but to have a cross-curricular view of how a strategy or approach would work outside of my own subject is really beneficial when evaluating.

Alternatively, you may coordinate a whole-school role and would like to support in how others in a similar role approach certain challenges or obstacles. Twitter was a fantastic place to seek out other literacy coordinators when I first took up the post; sharing action plans or discussing how we could collaboratively work on initiatives was fantastic for time-saving, mutually advantageous CPD.

Source a coach - and coach in return!

Peer coaching is quite possibly the most valuable method of professional development that I have undertaken during my time as a teacher. As a result of the fantastic coaching provision that the MTPT Project provided to me during my maternity leave, I am nearing the end of my first year as a coachee and will shortly receive accreditation that I can then use to direct appraisal discussion for this year. When setting up LitdriveCPD, a free coaching tool for the approaching academic year, my inbox was full of nervous-yet-enthusiastic teachers, excited and willing to sign up but worried that they didn’t have the required skills. Yet, as teachers, we coach every day: students, feedback provided to colleagues, ourselves even.

Find someone, either within your own school or one that you may network with locally, and see if they would be interested in informal peer coaching for the year. This could simply be three discussions over the year, with the focus upon you both forming your own goals, then exploring how you may work towards achieving them. The coaching role could be as detached or involved as both parties feel is necessary or appropriate, but the process of sounding out ideas with someone else working within the teaching profession could be really powerful to aid both your growth as a teacher, but someone else’s as well.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Why do you need to know about Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) for the school year ahead? It is the biggest cause of long-term sickness absence in the UK for students and staff. 21,000 children and young adults in the UK have the condition. You will have encountered an ME sufferer in your working life as an education professional, but do you understand what ME is?

To fully support students and fellow staff members achieve their potential, you need to understand that ME is a unique condition. Unlike many other disabilities, ME patients are unable to ‘push through’ or do ‘mind over matter’. Our bodies are lacking the essential life source that is energy. As hard as we attempt to fight against it, our bodies simply don’t cooperate because we don’t have the energy required to function properly.

What is ME? It is an invisible, severely debilitating neurological condition that affects 250,000 people here in the UK and 17-30 million people worldwide, and there is no effective treatment. ME is also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. The name given to each individual patient is purely dependent on who the GP is or where they live in the world. It is exactly the same illness. Personally, I refuse to use the name Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. as it doesn’t adequately represent my condition. Extreme fatigue is only one of over 60 symptoms that come under the umbrella of the condition. In the same way that you wouldn’t call Parkinson’s Disease ‘Chronic Shaking Syndrome’, I don’t believe our condition can be summed up as fatigue.

Symptoms include: post-exertional malaise, pain, cognitive issues, brain fog, memory loss, inability to control temperature, skin rashes, painful glands, and ‘flu-like’ symptoms. ME has a spectrum of severity ranging from mild to severe. This means that it is hard to judge what each individual sufferer is capable of. In addition to this spectrum, ME fluctuates. Our fluctuations can change by the month, week, day and hour. What we can manage at 10am may not be possible at 3pm. We don’t know when these fluctuations will happen, and that makes planning anything incredibly difficult and frustrating. This makes the condition very easy to misunderstand and disregard.

To the best of my knowledge, when a school encounters a student with ME they contact the school’s GP to ask for advice. The problem with this is that GPs receive zero medical training on ME. This was discussed by Parliament in June 2018 MPs agreed that training was urgently needed as students - and the M.E community as a whole - are suffering due to the inadequate knowledge of ME of healthcare professionals.

GPs are currently likely to recommend that students be encouraged to push themselves and attend school. This advice comes from a ‘treatment’ known as Graded Exercise Therapy (GET). GET has been proven to be extremely damaging to the health of ME patients, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have declared they are reviewing their guidelines in 2020. GET was debated in Parliament in February 2018, and Ms Carol Monaghan SMP, a former Science teacher, told how “the impact [of GET] on those with ME has been devastating” and her view that “when the full details of the trial become known, it will be considered one of the biggest medical scandals of the 21st century.”

GET is currently still recommended on the NHS Choices website. This is the website GPs use when researching ME and advising schools on supporting students with the condition. The ME community as a whole are heaving a sigh of relief that these guidelines are being reviewed, however it is worrying that so many more sufferers will be told to push themselves between now and 2020.

This notion of being able to ‘push through’ has caused students to be expelled, been told they are not allowed to go to the end of year prom, and fail qualifications because of the amount of school absenteeism and lack of appropriate support.

I have been an ME advocate for four years and have spoken at length to headteachers, heads of departments, and teachers who are worried that they are not offering adequate support to their students. Do they send work home? Would the student be able to attend school one day per week to keep up personal contact and relationships? How much work would they be able to cope with? Should they be given extended deadlines?

I can’t offer definitive answers. Only the ME patient can say what they can and can’t manage, and even then they may have unexpected bad days when all symptoms flare and make them bedbound. I have recommended offering a tailored approach. Flexible learning is a necessity, and allowing a student to work at their own pace is the only way they will leave school with qualifications.

I had ME myself aged 13-15. I was never diagnosed but - with hindsight - after contracting ME a second time aged 30, I know I had ME during my school years. Luckily, my school were very understanding and sent work home every week for me to complete. It was extremely difficult, but fortunately I am self-motivated and was happy to work with minimum instruction. I walked away from Secondary school with 9 GCSEs over grade C. I believe that there are many ME patients who are currently in school but are underachieving because their school isn’t as supportive as mine was, and who are having to battle for additional support when they should be concentrating on their health.

Post-exertion malaise is the defining characteristic of ME. Any activity can cause our symptoms to worsen - ME sufferers often call this ‘payback’. Our bodies are paying us back for using energy we don’t have. This could be an afternoon out with friends, or simply sitting and chatting over a coffee. It takes a lot of cognitive energy to hold a conversation; only people with limited energy understand that. Perhaps you have a student in your class whose parent has just called in to say their child is too sick to come to school, but you know they met up with their classmates socially the day before. This would be due to ‘payback’, but it is understandable that many would find it hard to believe that the student was genuinely sick.

It takes an incredibly long time to get a diagnosis if you are an NHS patient (mainly due to waiting lists). Patients undergo years of tests to rule out other conditions before getting a diagnosis. ME is basically what’s left at the bottom of the barrel. You may well have a student who has been ill for over 18 months and has high levels of school absence without knowing what is wrong. This is very common with ME. Our fluctuations and levels of severity make the condition incredibly difficult for GPs to diagnose.

My advice to teachers who this year have a student, or students, with long-term fatigue and long-term sickness absence is: support them, as soon as you can, irrespective of whether they are diagnosed or not. Quick and effective support increases the chances of ME patients going on to recover - or at least be able to maintain - a manageable level of severity. So many students have battled to attend lessons but have ended up making their health worse. Why battle to attend classes to get exams if you are so sick once you leave school that you are unable to work or are bedbound?

You can read more about Myalgic Encephalomyelitis on the ME Association website: www.meassociation.org.uk.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

School children are constantly engaging with their peers on digital technology and social networking sites such as Instagram, Snapchat and Musical.ly. While it is sometimes harmful - reports of cyberbullying cases are increasingly commonplace - digital technology also comes with considerable benefits. Below are some of the top e-health tools that enable pupils, and those supporting them, to access mental health and wellbeing advice at the click of a button.

1. Chat Health

This school nurse text messaging service was developed by the Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. ChatHealth is a confidential text messaging service which enables school children aged 11-19 to connect with their school nurse for help and advice on health and wellbeing issues, such as depression and anxiety, bullying, self-harm, alcohol, sex, drugs and body issues. Students will generally receive an instant confirmation message followed by a full response within one working day.

Find it at: www.southernhealth.nhs.uk/services/childrens-services/school-nursing/chathealth

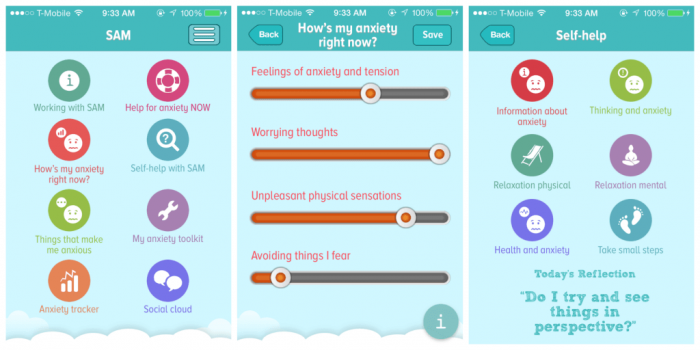

2. SAM

This is an anxiety management app created by the University of the West of England, Bristol. SAM helps users understand the causes of anxiety, monitor their anxious thoughts and behaviour, and manage their anxiety through self-help exercises and reflection. The app also allows users to share their experiences with the SAM community, and fellow anxiety sufferers, through a ‘social cloud’ feature.

Find it at: www.sam-app.org.uk

3. Worrinots

Created for Primary school children dealing with anxiety and worry, this app allows children to send a written or recorded message to one of four Worrinot characters: Chomp, Shakey, Rip and Stomp. The pupil’s message is then forwarded to a designated person at the school. The app can also be used by teachers as a tool to monitor their pupils’ wellbeing and provide early intervention where necessary. Worrinots was developed with the help of child psychologists, school staff and counsellors, and is Ofsted compliant.

4. WellHappy

An app for London-based 12-25-year-olds, this guidance and information resource contains details for accessing more than 1,000 local support services for mental health, sexual health, drugs, alcohol and smoking. Through the app, young people can also blog about their own experiences, read FAQs, jargon busters and information about rights and advocacy.

Find it at: mentalhealthpartnerships.com/resource/well-happy-app

5. TooToot

This platform and app, which offers ‘a voice for your students’, is an alternative way for students to report incidents of bullying, cyberbullying, racism, radicalisation, sexism, mental health and self-harm straight to their school, when they are unable to do so face-to-face. The app can be used by students (to report concerns directly to teachers), by school staff (to record incidents and behavioural concerns) and by parents (to report any concerns to school staff) Tootoot provides students with 24-hour support.

Find it at: www.tootoot.co.uk

6. ForMe

Developed with Childline by teenagers, this wellbeing app is aimed at children and young people, up to 19. Features include: access to self-help articles and videos on topics such as body issues, exam stress, emotions, bullying, abuse, mental health and self-harm issues. There is a message board where children can chat to others about what’s on their mind. Children can keep track of their daily mood through the app and tailor content that’s relevant to how they are feeling. If a child needs more support, the app will content them with a Childline counsellor for a phone or email conversation.

Find it at: www.childline.org.uk/toolbox/for-me

The year for progress

With teachers’ workloads persistently increasing, technology will continue to play an important role in enabling schools to screen for, and monitor, the mental health and wellbeing of their pupils. Apps and websites are essential in making effective use of teachers’ busy schedules and maximising their time with children: allowing face-to-face contact to be as targeted and beneficial as possible.

Access to digital mental health support also comes with an array of benefits for children, such as the ease, cost-effectiveness and swiftness in which these services can be tapped into. Additionally, digital technology provides an opportunity for pupils to share experiences with a group of like-minded people, fostering a sense of community and camaraderie.

While professional face-to-face services are still an essential part of supporting young people with mental health and wellbeing issues, digital support may be able to reach children who are unlikely to engage with mental health services. According to a 2016 Centre for Mental Health report, entitled Missed Opportunities, children are waiting on average 10 years for effective mental health treatment. Lastly, digital technology brings with it a level of privacy and anonymity - key for young people who are not comfortable to voice their concerns in person.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Online and in print, there is a lot of idealising about nurturing niceness and educating ‘the whole child’. But at the sharp edge in schools, when teachers are busy and pressured to provide results (test scores that is), what can realistically happen? Values and ethics reduced to a snappy slogan on the walls of the hall? Positive characteristics and traits referred to in a school mission statement but never in lessons? Sanctions imposed for negative behaviours but little recognition for positive? Rewards reserved for classwork and achievement?

In the same way that children need to be taught how to hold a knife and fork, tie shoelaces or do long division, so too are empathy, kindness, benevolence and charity traits that need to be taught. Yet where do we reward students for being kind and not just clever? Where do we praise schools for educating hearts and not just minds?

When asked “What is education for?”, the answer “passing tests” is not always at the top of list. Instead, teachers often cite ‘holistic outcomes’, citizenship development and rich understanding of knowledge in context - not just a list of rote-learned facts - as key ambitions.

But there is little reward for schools or students who achieve these holistic aims. Although evidence of healthy SMSC and British Values provision contributes to an inspection outcome, Ofsted’s criteria largely hang on exam results. Progress 8 looks at points from qualifications. SATs tests define a child’s Primary school achievements. Teacher assessment and reporting to parents leans heavily on levels.

How can we turn this system on its head? By innovating our routines and protocols. Happy children achieve more, kindness breeds kindness. Although ‘behaviour’ can be a key concern in school development plans, there is a difference between students not being naughty and being actively kind.

One method I’ve implemented had me standing up to present an assembly in front of Years 7, 8 and 9, playing a YouTube video called ‘random acts of kindness’ and then challenging students to conduct their own over the six-week half term. Media Studies students also created a video to show in form time.

The next half term we went a step further. On the first Monday back after the holidays, the school council and I went into school two hours early in order to (in the words of executive principal Dave Whittaker) “batter the school with kindness”. ‘Thank you’ notes left for cleaners and caretakers. Flowers in the reception. Fifty pence pieces sellotaped to the vendors, sweeties left in the staffroom, compliments stuck to windows. Free umbrellas for the rain, new pencil cases for the new starters, ‘you’re the best’ badges for the dinner ladies. Balloons dropped off at the nursery, handing Murray Mints to the arriving bus drivers, and a car cleaning service offered in the car park. The list was extensive, and I’ve forgotten a few I’m sure, but the buzz was tangible.

With the school council driving the agenda, students let their imaginations run wild with the kindness drive. A school charity was formed - ‘The Helping Hand’ - and projects dreamed up. Age UK and Yorkshire Air Ambulance visited the school, collections and visits to local food banks were run... It was a beautiful blooming of positive deeds, and served to remind staff and students: ‘It’s nice to be nice’.

Other projects/ideas to promote kindness in schools:

The results were striking. There were 100s of recorded and rewarded acts of kindness. Students could see them, staff could see them, and we could all feel them.

Here are just some acts of kindness by students recorded by staff over two half terms [this is a fraction of the acts Paul sent in! - Editor]:

Where is the kindness in your curriculum? Make this year the year to be nice. World Kindness Day is November 13th 2018, and Random Acts of Kindness days can be run throughout the year, so get planning!

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

An NUT survey in 2015 found that over half of teachers were thinking of leaving the profession in the next two years, citing ‘volume of workload’ (61%) and ‘seeking better work/life balance’ (57%) as the two top issues causing them to consider this. Research also shows that one in four teachers will quit the profession within the first five years of teaching. Yet, according to a Gallup survey in 2013, teaching was still voted number two out of the top 14 careers - beaten only by physicians.

Why did you go into teaching? Most of us came into it because we had a vision of how we thought education should be. We loved children, believed that we could affect change, had an enthusiasm for our subject, and we wanted to make a difference. Sadly, many of us have lost sight of that vision.

Consider this: On a scale of 1-10, how stressful is your job? Too often, we do not listen to our bodies, ending up with distress, which manifests physically as pain, muscle tension, injury or disease; emotionally with symptoms of jealousy, insecurity, feelings of inferiority, inability to concentrate, poor decision making, mental disorientation, depression, anxiety and so on.

In this article, I’m going to outline five steps to create delicious habits that will make you positively flourish at work!

1. Put your own oxygen mask on first

I am sure you will have heard it said, in the preflight demonstration, that if there’s an emergency, to put on your own oxygen mask before you help others. The idea is that you don’t become so preoccupied with trying to help secure everyone else’s oxygen mask that you forget to secure your own. You are not going to be much help to anyone, let alone yourself, if you’re in a pre-comatose state!

Teachers and school leaders often tell me they have depleted themselves for the sake of others - pupils, management, staff, family, friends. It’s important to take the time and care to secure your oxygen mask, then when the challenges of school life come hurtling towards you, you will have some foundations with which to deal with them.

2. Eat a healthy, balanced diet

Drink water throughout the day. By staying hydrated you'll be taking care of your most basic needs first. Water is also essential for cleansing the body, so try to drink at least four to six glasses a day.

Cut down on all refined and processed foods, sugar, fried fatty foods, additives and all stimulants like tea, coffee and alcohol. Instead, eat more whole grains, vegetables, fruit, whole wheat pasta, seafood, free range/organic poultry and dairy products. Make sure to eat enough to ensure your blood sugar isn't crashing. Have healthy snacks around, especially when you are ruled by your school breaks and busy schedules.

3. Start an exercise programme

Walking, running, swimming, aerobics, dancing or yoga. Exercise regularly at least twice a week. There’s a lot of research out there that indicates the better shape you are, the easier you will find it to handle stress.

4. Take time off from the digital screens

While screens may feel relaxing, and allow you to turn "off", try and find a sans-screen activity to truly take time for yourself. Skip the TV and enact even the smallest self-care rituals, like:

5. Say “NO!”

This is the hardest word for a teacher to say! Most of us are kind and caring individuals, high achievers and hugely diligent. We teach because we want to make a difference, and the word ‘no’ is so hard to say. But we MUST say it if we are to survive in this culture of an ever-increasing workload. Try saying: ‘Not now’, and then give a future time frame.

Take Nottingham’s Education Improvement Board as an example. They have come up with their own fair workload charter. In brief, the charter defines what ‘reasonable’ means in terms of the additional hours teachers are expected to work beyond directed time each day. They say that school policies should be deliverable within no more than an additional two hours a day beyond directed time for teachers (and three hours a day for those with leadership responsibilities).

Schools adopting the charter receive the Education Improvement Board fair workload logo to use on their adverts and publicity. This reassures potential applicants about the workload demands that will be placed on them in choosing a charter school over one that hasn't adopted it. Read more about the charter at: www.schoolsimprovement.net/what-exactly-is-a-reasonable-teacher-workload.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

Every September, when greeting my new class, I would follow the same pattern for the first two weeks to settle them in. I don’t think there is anything magical or mysterious about how I settle children and classes, so I am going to share it now, so that anyone can pick up the bits they think they would find useful. I should also give props to my mum here, as I learnt about routine, expectations, and consistent boundaries by watching her as a childminder to toddlers!

Some of you will read this and think “Well, she has never taught in a challenging environment if that works”, but I can assure you that, having worked at inner-city London schools, this settle-in routine was a necessity - not a ‘nice-to-have’ - and there were certainly some very challenging cohorts who I thought this would never work for. But I always persevered, and it always came good in the end!

For me, settling a class is about four main things:

Getting this right in September means not having to be strict all year. I was known for having very high behaviour expectations with my classes. But also, anyone visiting my class to observe during the year could not actually pinpoint what I was doing that they would consider ‘strict’. The reason is very simple: I had done all of my settling back when no one was watching! So now there is nothing to see. They know the rules, and I know what they are capable of.

The introduction

The first thing I would do with my new class is a little speech. Here, I explain that I have three jobs. ‘Teacher’ is my job title, but it is actually my third job once I have completed the first two. The first job I have is to keep them safe. At the very least, your parents expect them all in one piece at hometime each day. Being safe is about the safety of everyone. Individual and collective responsibility. Running around in the classroom = unsafe. Holding scissors aloft while chatting = unsafe. And so on. So any behaviour such as that would stop any lesson immediately (anything which stops a lesson causes a sanction).

My second job is to ensure everyone is happy. This is not to be confused with my job being to MAKE people happy. It is not about having fun or being entertained. Happiness is more a contentment - it means that we care about everyone around us, and show everyone respect in their classroom and learning environment. Someone crying due to someone else ruining their drawing = I need to intervene. Someone upset or angry due to being annoyed by someone else in class = I need to intervene. Again, intervention by me means learning time lost, so could result in sanctions.

The other part of happiness looks at my commitment to intervene - and support/help - if a child is unhappy due to circumstances outside of the classroom. No need to labour this point, but it is worth the pupils knowing that, say, if they arrive angry after a fight with siblings, they can sit and calm down in the book corner before register, to get happy for school.

Once my first job (safety) and my second job (happiness) are done, I can then teach. Those conditions mean we can learn loads. We can discover exciting facts. We can learn about interesting places or words. I commit to always making lessons as engaging and interesting as possible, but making sure pupils learn from them is the main objective. Pupils must commit to working hard and listening, and I will then support them as much as a I can to help them succeed.

Once the speech is done, we usually spend that first lesson drawing up a class agreement based on my speech outlining the above. The rules come from them based on the “safe” and “happy” criteria, ie “We need a rule about hurting people, because that could make things unsafe AND make people unhappy.”

Time to get to work

The next two weeks are carefully planned to include lots of independent working. The reasoning is threefold:

For each of the independent task lessons (at least two a day in the first two weeks) I would, of course, do some teaching up front. After this, I would have various tasks which were very low-challenge or significantly differentiated, so that everyone could access them without support. The tasks quite frankly would be considered, at any other time, to be a total waste of learning time. I make no bones about this. But at this stage in the term, it is vital for me to do this so that for the rest of the year my learning environment allows us to have extremely high expectations.

So during the silent lessons, I will pick up on every single issue of behaviour. I mean every single one. In each case I would never call the child out publicly. While the class works I sit at the desk and work with individuals. I call them over, ask why they think they did the right thing. I will explain my expectations. If it is something a previous teacher allowed but I will not, I explain to the whole class that I understand they were allowed to do that before, but in my class I don’t allow it - and I always explain why, referring to the rules (being careful, of course, not to undermine the previous teacher, but just to say we are different). We set up agreed new routines as a class so that expectations going forward are clear.

Once we have done a few silent lessons the majority of children are now on board and understand that you mean what you say - this is the first turning point. They now start to remind others of the expectations. They start to keep each other on track with other teachers (PPA time) too. Then we can start to spend more time with the more “spirited” children who need a lot more support in settling.

You might even end up spending a lot of time with one or two key characters who seem to be always at your desk during silent working, having been called up for one misdemeanour or another. This time is really key. It gives you a chance to give them attention they clearly need, without it interrupting your main curriculum later down the line. I have had cases where, even right near the end of the two weeks, there is just one or two children I cannot seem to get the right connection with. Some of these go on past the two weeks. But by then, the rest of the class is 100% onboard and actually enjoying how settled and calm their class is. So they do not mind you spending extra time with one.

And this time with the more disenfranchised pupils really works. They eventually realise you mean everything you say. They see you start to loosen up with the rest of the class, and that you really won’t be strict forever if everyone does the right thing. They see you being fair and consistent with everyone. They see you wipe their slate clean and start again every single day. So eventually they trust you, and order is established with everyone. The side effect is also a more cohesive class who work together calmly.

As I said, this may not work for everyone. And in a short article I have had to speed up the explanation, but hopefully the intention is clear and the tips will help some new teachers. Get in touch if you want to find out any more ([email protected]), or discuss any challenges you are facing when settling your class - I am always happy to help!

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

There were two turning points for me that I distinctly remember. The first was in September 2014 on our INSET day. We’d just hit 85% 5A*CEM in the summer, been awarded Outstanding in every category in July, a far cry from Special Measures and 28% three years previously. Behaviour had been described regularly as ‘feral’ but was now brilliant. I announced as much to my staff, then followed with the line that would change our strategic direction:

“But is anyone having any fun?”

I didn’t regret the sledgehammer approach we’d had to take with the school to turn around engrained and endemic inadequacy, but I knew things had to change. Regional Harris director Dr Chris Tomlinson once told me that a head’s job is to make themselves redundant and this principle resonated strongly. If I got hit by the proverbial bus, the school would be stuffed. It was therefore not sustainable.

My question, and challenge, to staff was to begin our journey to create a school that the staff truly wanted to work in, where we could feel the buzz of burning ambition and professional success, the warm glow of helping the most vulnerable in our society change their lives, the pride of being part of a story that is changing our part of South East London. But with no burnout. Ever.

We started by collating all the reasons why staff wanted to work here, in our school, rather than anywhere else. I’m a big believer in your internal brand matching your external brand - by this I mean what you SAY you do, you ACTUALLY do. Staff can sniff out spin a mile off and it truly stinks, breeding cynicism and resistance throughout the organisation.

To avoid this we spent lots of time making sure our ‘20 reasons to work here’ was actually real for staff. I asked them to rate the three reasons that were most resonant and the three that felt furthest away. I then gulped, and shared it with all the staff; one of my mantras being “no elephants in the room”. We then openly discussed the issues and what to do about them. Only when we were completely sure about them did I have them branded for our recruitment strategy.

I regularly review these 20 reasons to make sure the school has not drifted away from what we say we do. We place huge value on integrity and ensure it runs through every decision, every conversation. Holding ourselves and each other to account does not have to involve being needlessly brutal - when you do it with integrity and honesty suddenly, it is much more powerful and does not corrode trust.

Three years later the school was in a great place. Staff morale was high. We were ‘bringing ourselves to work’, another of our mantras; great banter and belly-laughter was encouraged; the hierarchy was flatter.

And this leads me to the second turning point, shortly before we broke up for summer holidays last year. Speaking to my coach, I realised something else was missing.

Life.

I was talking to her about how I hadn’t seen my kids for four days as I kept missing their bedtime, and that I was going to leave early that night at 5.30pm so I could see them for half an hour. But I was filled with anxiety about how I could make that happen and what example that set - would the staff think I was lazy and not earning my salary? My coach asked what time I'd arrived that morning: 7.30am. She asked me if I’d had a break: of course not, I’m SLT. Then she asked the killer question:

“At what point did working ten hours a day stop being enough?”

The penny dropped. And this might be controversial. You see, while I am indignant at successive governmental failures to recruit enough teachers, I do believe that too many schools have not done enough to ensure that teaching remains a fun and highly rewarding profession. Often, we’ve allowed ourselves to be bullied, to become scared of Ofsted and the DfE and bad press. It’s therefore totally understandable that, on occasion, we’ve wielded the sledgehammer approach for too long, too hard, too often, too carelessly.

Don’t get me wrong. Headteachers should hold people to account. Those who are completely incompetent should be drummed out of our proud profession by all of us. We should drive high standards for ourselves. We should expect the best for our children. They deserve the best. But we don’t have to run cultures of fear and we don’t have to break our staff.

It so happened that John Tomsett, a headteacher I very much admire, was getting some well-deserved attention for the great work his school was doing on addressing workload. I took his list of ways to reduce workload to my SLT and we realised that we were doing nearly everything on there, and more. Just not consistently or mindfully enough. So again, like we did with the ‘20 Reasons’, I now took the ‘40 ways we reduce workload’ to the staff to ensure they were resonant. I also set them the challenge for this year: “If you’re still here after 5.30pm, something in your own system, your department’s system or the school system has failed. Then let’s fix that.”

By being open and honest about the challenges we face, getting the systems right, being efficient and streamlined in our approach, we’ve been successful in changing the culture: the vast majority of staff in a recent survey said they had a healthy work/life balance.

So what needs to change across the school system to make our working lives more productive, more meaningful, less frustrating and less exhausting? Read our ‘40 ways we reduce workload’ and let me know what you think. Share your ideas to make them even better. We’re really trying to make it happen at Harris Academy Greenwich and I don’t believe our results will suffer.

It has been an eight year journey to lead the school to this point where the systems are tight, the staff are slick and well-trained, the school purrs. We have fun, we laugh, and we don’t break. Ever.

I love teaching. I love life. It’s possible to have both.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!

With the exponential rise of technology, the popularity of social media platforms and the ubiquity of smart devices, ‘online health and safety’ has never been more important. The benefits of edtech are enormous, from individualised learning and mixed realities, to the instant global connectivity that social media provides. But we need to balance these rewards by addressing the risks of being online - from cyberbullying and loss of privacy, to concerns around the mental health of social media users. So how should schools go about ensuring this?

There is a parable about two woodcutters. Determined to prove their superiority, they decided to have a competition to see who could cut the most trees down in one day. One woodcutter chopped on relentlessly, spurred on by the intermittent silence of his competitor whom he assumed was exhausted. But when the day ended, he discovered to his horror that his competitor had felled twice as many trees! His competitor had triumphed, simply because every-so-often he had taken time to sharpen his axe.

I write this at the start of April, whilst enjoying a view some may call “paradise”: sat on Long Beach, in Pulau Perhentian Kecil, with the South China Sea lapping up against my toes. It’s been a well-needed ‘switch off’ after the last three-to-six months (the last three in particular). The added benefit of five days without working WiFi was not lost on me. Whilst naturally there were those who worried about my radio silence, being blissfully ignorant of literally everything going on outside of a 1km stretch of beach has been quite refreshing! So how has this benefited me as an international educator?

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom