Too often source analysis has been placed into easy-to-define statements. “It is a cartoon therefore it is mocking…”; “It is a drawing therefore we can’t be sure it actually happened…”; “It is from a historian therefore it is well researched and balanced…” Or perhaps worst of all, “the source is biased”. Instead of pulling my hair out at these statements which, apart from the word bias, all could be vaguely applicable to the source in question, I wanted to understand why students fell back on these phrases and why teachers taught them.

In part this is because true source analysis comes from being able to place yourself in the shoes of the person writing the source. That ability is problematic for students - particularly if Piaget is to be believed, when he said that students do not develop conceptual understanding until they are fourteen. Therefore they cannot imagine they are someone else.

This is then compounded by the fact that a lot of sources tend to come in a written form. Now, whether that is archaic language (simplified or not) or a more modern interpretation on an event, the problem for students is in the nature of the source. It’s just like emails and texts from being people that you do not know, meaning can be misconstrued easily. Implicit messages are not picked up on because - firstly - this is not the main type of communication nowadays and - secondly - students cannot place themselves into the mind of the author whether they know of them or not.

Strategy 1

If studying whether or not Edward II was murdered or escaped to Italy, I needed my students to understand the people both behind the investigation and indeed behind the source. Now, I am unfortunately not one of“I wanted to understand why students fell back on worn-out phrases.” these amazing teachers that comes into lesson and can embody a character, treating students to a real insight into that person. Nor do I have the curriculum time to do this over a series of eight characters (four weeks). However, I can embody them in front of a camera with no one watching.

To do this you need to have a quiet space, allow for lots of retakes and, most importantly, prepare your script beforehand. The real gift is to try and drop the implicit inferences through visual cues such as tone, intonation, eye contact (or lack thereof) that students will pick up on which allows them to look for meaning behind the dialogue.

Result 1

Once they know that something is afoot, students can start probing the material deeper, asking the key questions like:

- “What has gone on beforehand?”

- “When did he say it?”

- “How does it fit in the chronology of events?”

- “Who is he affiliated to?”

- “What is the purpose of the source?”

By providing accessible interpretations of past characters you not only make the story come to life, but you also create a vehicle for students to want to delve deeper into the past through their questioning of the material.

This allows them to start developing a web of links between characters, producing work that reaches substantive judgements based on high level source analysis that is well-developed.

Strategy 2

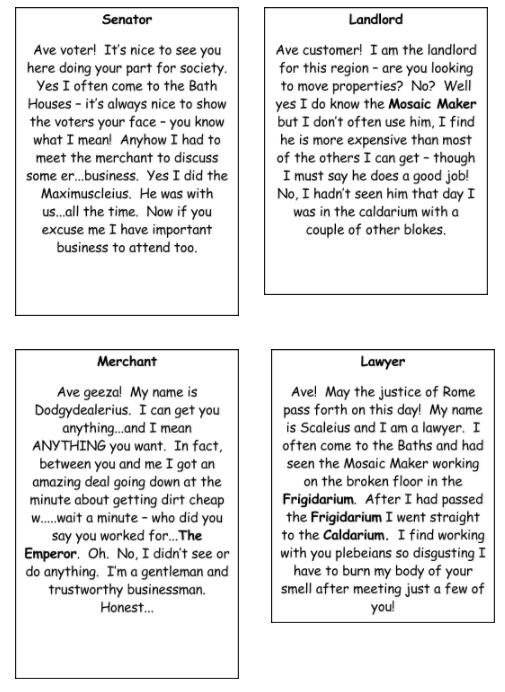

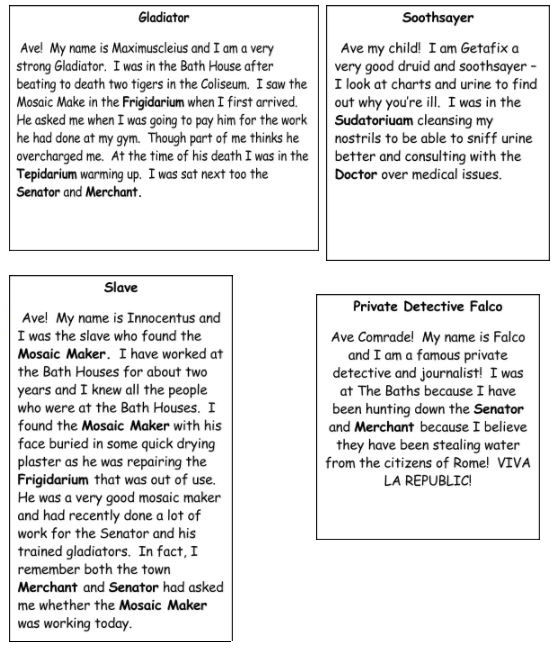

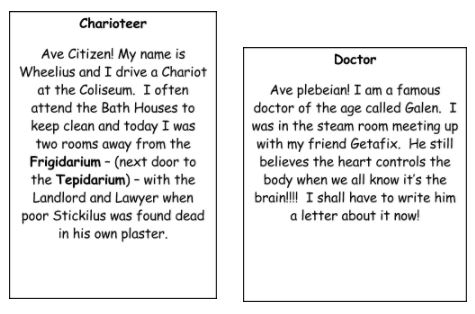

Clearly this cannot be done for every lesson, but I would advocate that rather than adapting sources based purely on language that you adapt it so that it is more conversational English. In a lesson to introduce public health in Roman times, I created an investigation into the murder of a fictional character called ‘Stickilus’ who stuck Mosaics to a wall. In these sources below, I added text so that pupils could see literary plot breaks in answers and start to question why that was.

Result 2

This allows them to study 11 sources and reach a conclusion that it was the Gladiator (Maximuscules) in conjunction with the Senator and Merchant (Dodgydealirous) who had a secret cartel that Stickilus had uncovered. This ability to cross reference source material and come to a substantial judgment and the answers they produce are of the highest order.

Above all, I believe in this approach in Key Stage 3 because I have seen the results of this immersion in their ability to analysis sources that are more complex as they develop. They start asking the right questions of source material, and start making good judgments as a result.

However the overriding reason I believe in this is because it allows them to encounter so many of the great mysteries of the past and have their say on them. It builds a thirst for knowledge and empirical enquiry that goes beyond the classroom. By selecting a form of sources that is accessible to them, they can see the best stories in history and we can see their best analysis.

Resource: Romans Who Killed Stickilus cards

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!