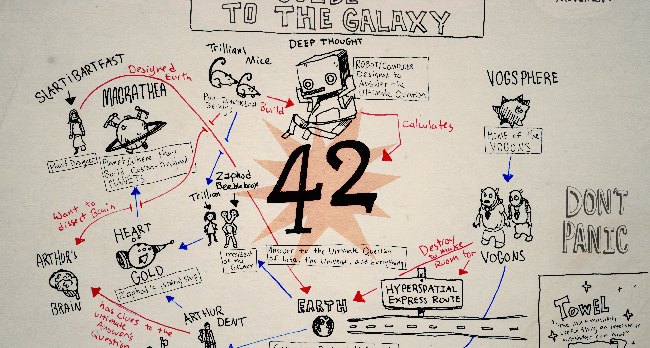

The ultimate answer to the ultimate question is found to be 42 - genius! Why not 42? What could 42 represent? What is the significance of this number in relation to life, the universe and everything? The answer requires investigation, probing, further questioning and imagination. Teachers can learn much from Adams’ work.

Beyond the Vogon Checklist…

Our vogons are also on the lookout for questions. With no imagination, these creatures are only capable of running things; they have forms to fill and boxes to tick in their search for outstanding. There is a box that tells them they should see questions in outstanding lessons. A lack of imagination could see them awarding the use of any old questions, questions with no purpose other than to elicit a right answer.

Do not worry about them. Once their boxes are ticked, they will move on; what you need to know is that there is so much more to questioning than simply producing a right answer. Questions posed by teachers that lead to debate, controversy, interrogation and dispute are an amazing tool to have in the armoury of pupil progression and, once you have mastered questioning yourself, teaching pupils to ask their own questions could change the world.

From Earth to Space

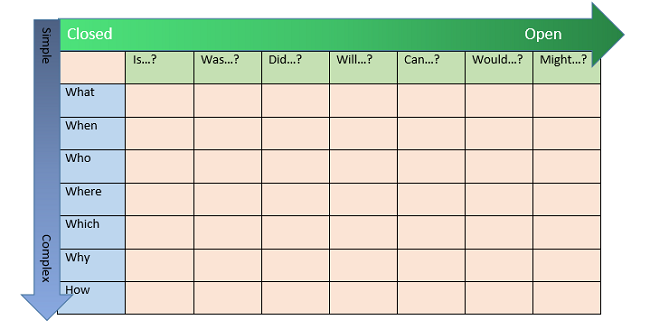

Taking your questioning to an intergalactic level will require you to become a question expert, knowing the purpose and outcome of each question you ask. Lower-order questions tend to be closed, with single, defined answers. If you want to test what a pupil knows, these questions can be useful; if you want to change the world, you are going to need questions of a higher order. Higher order questions allow for debate, argument and query. These questions can lead to new discoveries and the unlocking of imaginative potential.

Simple question grids can allow you to recognise what kind of question you are asking. Create question stems using the grid and display them around your classroom in order of complexity. When you form a question, you will be able to see at a glance the level of your questioning. You can use your wall display to devise and also rephrase questions, matching them to individual pupils’ abilities.

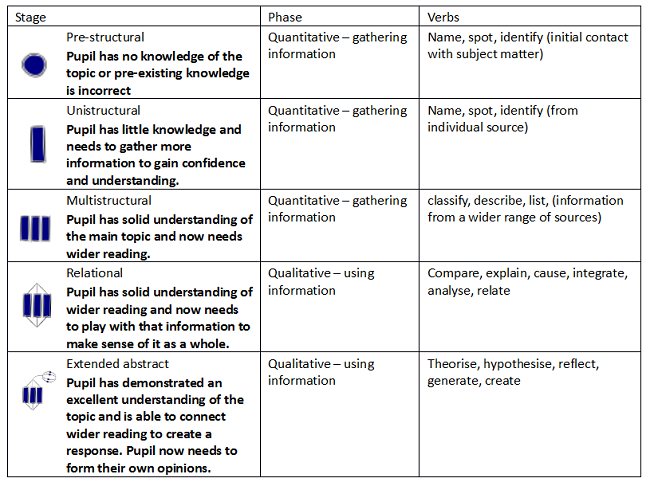

Using taxonomies such as Bloom’s and SOLO can also support you in recognising levels of questioning and the intended outcome of your questions. Each taxonomy comes with action verbs attached to particular phases of learning. Using question grids alongside an understanding of learning complexities can allow you to categorise questions to ensure they are fit for task.

For example, if I ask “When did Hussain die?”, I am asking a simple, closed question according to the question grid, and I can see that I am asking pupils merely to “identify” a specific time. This is a closed question which has only one purpose; to allow me to see if pupils possess this knowledge. If I want to challenge pupils’ thinking and get them debating and creating new responses, I can use the question grid to form an open, complex question such as, “Why might Hussain’s death have changed the world?” I can check my intended outcome using the verbs and see that I want pupils to “hypothesise,” a much higher order skill.

Never underestimate the usefulness of knowledge. SOLO taxonomy asks pupils to build their way from gathering knowledge towards creating their own ideas with that knowledge in mind. Pupils learn to recognise the importance of their multistructural knowledge in creating quality responses. Do not expect pupils to be able to change the world successfully if they have no knowledge of the world in which they live. If I was to ask pupils to hypothesise about Hussain before they had learned anything about his context, they may produce prestructural responses to an extended abstract question; such responses may be interesting and different, but may not be useful.

When no questions are asked, no new thinking occurs. During Arthur Dent’s journey through the galaxy, his home planet was destroyed due to a lack of asking questions. A form was filled in and an order was carried out. Bypasses had to be built and nobody questioned ‘why?’ Nobody asked if there was a better, less destructive way and, as a result, nobody saved the earth.

We currently live on a turbulent, overpopulated planet. So rooted in the dogmas of the past are we that we often fail to ask questions, accepting that things are the way they are because that is just how it is. Education needs to shake off the dogmas of the past and evolve to ensure the survival of our species; the future citizens of the world need to be innovative, creative and they need to be unafraid of asking questions.

What to do to with Arthur Dent

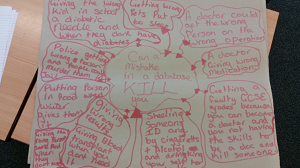

Arthur is cynical and fearful of change. To open his mind, you will need to begin the questioning for him. I recently worked with a teacher of ICT who was struggling to get a room full of Arthurs interested in spreadsheets. We created a question that, like the answer 42, would lead pupils to ask more questions. The question we created was “Can a mistake in a spreadsheet kill you?” To ensure that everyone took part, we planned to use escalator questioning to begin the investigation.

Pupils sat in silence at first, reading the question before reaching into a ball pool full of question stems. Their aim was to create as many questions about the original question as they could. After a few minutes of lone questioning, they paired up and created a list of joint questions, adding more as their discussion developed. The pupils then created groups of four and used their questions to answer the original question. By beginning alone, pairing up and eventually getting into a group of four, more questions were created and everyone contributed to the final discussion.

What to Do With Zaphod Beeblebrox

Unlike Arthur, Zaphod will throw himself into any task you give him. However, having only half a brain, he needs a little extra support in creating his questions. Creating a question grid for Zaphod will allow him to ask questions, but also recognise the quality of the questions he has asked. For example, in Citizenship, the teacher has, as above, began a new topic with a big question.

This time, the subject is human rights and a picture is chosen to stimulate discussion of a killer caught on CCTV. The teacher does not reveal that this is a killer until much later. The big question is, “Is it okay for the government to spy on us?” Zaphod’s gut response is to simply answer, “Yes.” Having a short attention span, he likes to rush tasks; knowing this, his teacher has banned all conclusions until at least twenty new questions have been asked.

For support, Zaphod is given a question grid, printed out and laminated so it can be easily reused. The teacher drip-feeds more information about the original image in the form of thought bombs. A thought bomb can be made by cutting a hole in a plastic ball and filling the ball with new information.

When the bomb is thrown to the group, it should explode their current thinking and make them ask more questions about the situation. Drip feeding information in this way will support the consideration of individual bits of information. Using the question grid, Zaphod is able to ask, where was this picture taken? Why would the subject of the picture want to hide their actions? Does it damage us to be watched without our knowledge? The conversation on Zaphod’s table is rich and the questions asked are varied, leading to varied and interesting responses. After twenty questions have been asked, Zaphod can see how useful the questions were in forming a rich response as opposed to his original one word answer.

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe

Pupils who have closed their mind to the possibility of intelligent flying dolphins and aliens that can kill you with poetry may leave school and join the queue, standing in line, awaiting their unremarkable deaths. When someone turns up to demolish their homes, making way for a bypass, they will accept the inevitable and take it lying down. Teaching pupils to question the world’s possibilities, to explore the probabilities, ignoring the first answer and looking out for the unlikely, we can keep their minds open and open them up further still. Pupils who learn that it is okay to ask why bypasses have to be built in the first place will leave school asking questions that count. Open-minded pupils with a zest for questioning will have lunch in the restaurant at the end of the universe before asking the questions necessary for solving the problems our future world will face.

How do you tackle questioning in the classroom? Share your methods in the comments.