In terms of an itinerary, it is important to visit cemeteries covering a range of nationalities. This reinforces the overall human tragedy of the conflict and resonates much more strongly than getting students dressed up in British khaki uniforms and marching around Commonwealth cemeteries for several days (which is only marginally less tasteless than visiting German sites in the same garb – and believe me, these sorts of trips do happen). For the French dimension I spend time at Notre Dame de Lorette, which is the world’s largest French war cemetery. It contains the remains of approximately 35,000 soldiers which represents just 2.5 percent of the estimated 1,398,000 French war dead of World War One. An imposing ossuary contains the coffins of Unknown Soldiers from the Second World War, the Concentration Camps, Northern Africa, and Indo-China.

In terms of British cemeteries, Tyne Cot in the Ypres Salient is the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the world. However, the horrendous nature of the fighting at the Battle of Passchendaele means that a very large proportion of the graves are for Unknown Soldiers. For this reason I make a particular point of visiting Lijssenthoek cemetery, which contains the named graves of men who died in casualty clearing stations away from the fighting. The difference here is that the personal inscriptions on the gravestones make for a particularly powerful experience. Also at Lijssenthoek are 883 war graves of other nationalities, mostly French and German, and the final resting place of a female nurse, Nelly Spindler, who was killed by a stray shell in 1917 and whose story reminds us that women too played an important role in the conflict. Another Commonwealth cemetery well worth a visit is Ayette, which contains the graves of Chinese and Indian labourers (a total of 2,000 Chinese and 1,500 Indian labourers died while serving on the Western Front).

The German perspective can be addressed by a visit to Langemarck, the only German cemetery in the Ypres Salient, containing 44,292 burials. The first large headstone is a mass grave containing 25,000 soldiers. Flat stones mark burial plots: often up to eight soldiers share a (sometimes unknown) grave. The contrast between this site and the Commonwealth war cemeteries is stark: rather than the white Portland headstones and manicured grass reminiscent of an English country garden, Langemarck is dark, foreboding, with black headstones in permanent shadow from heavy oak trees. It conveys the sense of utter desolation felt by many Germans at the end of the war – for they, unlike their enemies, did not even have the scant consolation of a final victory in 1918. That sense of national trauma fed into the desire for revenge which propelled Hitler into power: and it is notable that in 1940, during the conquest of France in World War Two, Hitler spent two days in the Ypres Salient (where he had fought himself) and concluded his trip with a visit to Langemarck.

As well as comparing the way that different national perspectives on the war are reflected in the cemeteries, there are also the memorials to the missing from different nationalities that can provide further material for reflection. The Thiepval Memorial on the Somme, and the Menin Gate in Ypres, are the most notable British memorials (and the latter has in its grounds a particularly moving memorial to the Indian forces that fought in Ypres). The Canadian memorial on Vimy Ridge (pictured above) is breathtaking in scale and artistry, and provides an interesting contrast since it focuses at least as much on the impact on women as on men. The South African memorial in Delville Wood is particularly interesting since it reminds us that this was not a war between the forces of democracy against the forces of dictatorship: the British and the French were not only allied with autocratic Russia, but South Africa was a member of the Commonwealth despite being an openly apartheid regime. This serves to remind us that the values which we hold dear – democracy, tolerance, equality – were not necessarily the same ones that were being fought for between 1914 and 1918.

To complement the cemeteries and the memorials to the missing, there are other sites that highlight different national dimensions of the conflict. Outside of Albert lies the Pozieres Australian memorial, whilst the Ulster Tower just minutes away from Thiepval honours Northern Irish troops: it offers snacks, a picnic area and, best of all, a spirited talk from its long-term guardian, Teddy Colligan. Just a stone’s throw away is Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park, which provides guided tours of the battlefield where the Newfoundland Regiment suffered such heavy losses during the Battle of the Somme. Talbot House (pictured below), which is situated just outside Ypres in Poperinge, was a refuge for British soldiers during the war and which has been kept ever since as a permanent memorial. As well as providing a reminder that there was more to the war than just the fighting, it offers an excellent guided tour, picnic tables and endless pots of strong English tea (presumably of the type that the Kaiser immediately asked for upon arriving in exile in Holland in 1918).

A varied itinerary is not the only way to ensure an international focus to a successful Battlefields trip. Another technique is to read a range of poems at different sites in the original language (with a translation afterwards if appropriate). Wilfred Owen’s The Sentry was written at Serre, which is a site worth visiting on its own terms for its memorial to the “Accrington Pals”. Siegfried Sassoon’s Aftermath (“Have you forgotten yet?”) is always the poem I end the trip with. However, I also make use of Eugène Dabit’s French poem I Became A Soldier at the Age of 18 at Notre Dame de Lorette, whilst at Langemarck a student reads Alfred Lichtenstein’s Prayer Before Battle in the original German. What is striking is that whatever their nationality, all these poets share the same fears and hopes about the war and once again this helps to drive home the point that above all this was a human, not a national, tragedy.

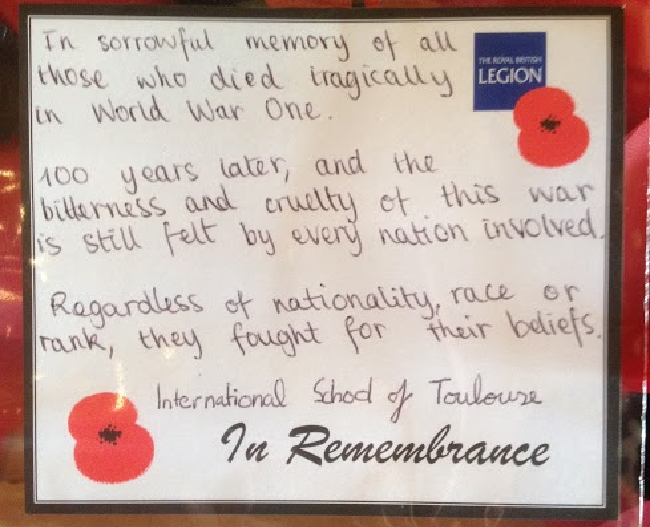

In this spirit of open-minded reflection it is also worth purchasing a commemorative wreath from the British Legion website (which can be delivered to your school) and make an application to lay a wreath at the Menin Gate in Ypres during the nightly Last Post Ceremony. In advance of the ceremony, students should discuss exactly what to write on the dedication slip. By this stage it is unlikely that many students will want to write anything narrowly nationalistic or triumphant. To get them started, I provide my own students with the following writing scaffold:

First sentence: Choose one word per line, or add your own.

In [proud | grateful | sorrowful]

[memory | honour | recognition] of

[British | Commonwealth | All]

[People | Soldiers] who

[Died | Suffered | Served]

[bravely | needlessly | tragically]

[in the Ypres Salient | on the Western Front | in World War One | In the World Wars | In all wars]

Second sentence: complete this sentence in your own words.

They died fighting for…

The quality of discussion, and the dedication that then emerges, never fails to impress: my students this year settled on “In sorrowful recognition of all the soldiers who died in World War One; those who fell with their brothers, those who came home, and those left behind. They died fighting for peace, patriotism and pride. Let them be defined by their lives not their deaths. They made the ultimate sacrifice for peace. Never again”.

Another idea that works particularly well is to purchase some commemorative poppies, and give one to each student on the trip. At one of the cemeteries of their choice, each student places their poppy on a particular named grave based on how moving they find the particular inscription. I have found that students welcome the opportunity to place their poppies on a range of national memorials: German students in particular find particular poignancy in paying their respects to German soldiers whose story is too often treated with insufficient respect due to their status as ‘the invader’. An extra dimension to this exercise comes from purchasing not just red poppies from the British Legion (which broadly honour the noble sacrifice made by Commonwealth soldiers) but also white poppies from the Peace Pledge Union (which stress the pointless waste of life that characterised the war). Students can then choose not just where to place their poppy, but also the particular message about the war that they wish to convey.

Thought should also be given to follow-up work once the Battlefields Trip has finished. For example, I have worked closely with the art department in the International School of Toulouse to help students design and execute an art exhibition relating to the trip. The students volunteered to produce panels, sculptures, dramatic pieces, artworks and collages about the trip along with a visitor guide for the exhibition. Younger students were then given guided tours and an activity booklet. Each student was also given a ‘character card’ that told them about the life of one person during and after the war – some of whom were men, some women, all from a wide range of nationalities. Their task was to find out the name of their character by matching up their card to one of the character cards’ on display on the walls: these cards told the story of the lives of people before the war. This encouraged students to read about many more life experiences than might otherwise have been the case.

Another follow-up activity is to help students to deliver an assembly near Remembrance Day. As far as possible this should encourage students to reflect and form opinions on key questions relating to the nature of ‘remembrance’. Such questions include: “Should we remember the actions of soldiers, or civilians involved in war too? Should we remember all conflicts, or focus on specific ones? Should we remember people on both sides of the conflict, or just those on ‘our’ side? Should we remember wars that ended badly for ‘us’ as well as those that we ‘won’? What should the money raised from a poppy appeal be spent on? Are we ‘remembering’ that war is sometimes necessary, or that it is always pointless? Should we wear a red poppy, a white one, neither or both?” Following this assembly, each year group then has a different PSHCE lesson covering a theme relating to remembrance – with the result that every student gets a fresh perspective as they progress through the school. This is now a well-established part of the school curriculum and is complemented by a similar suite of materials for Holocaust Memorial Day.

Different schools will devote varying amounts of time and emphasis to their personalised Battlefields trip, and the experience is so rich in potential that I have inevitably covered only a small proportion of sites and approaches.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!