I’ve spent the best part of my career in Secondary schools and colleges trying to stop myself falling into this situation, up to the point of appointing one student in every lesson to be on ‘Petewatch’, letting me know whenever I spoke uninterrupted for more than five minutes.

Why do teachers like talking?

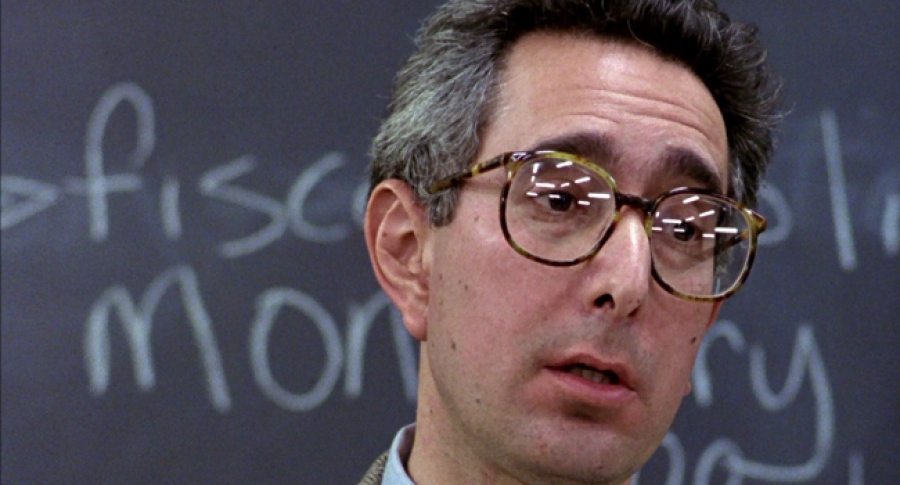

"Many teachers find student involvement in learning very time-consuming."

First of all, they love their subject – that’s why they teach it. Talking about it at length is a pleasure that is just not appropriate at dinner parties and other social occasions. Most teachers enjoy talking too: many quite like the sound of their own voice, and have developed the ability to keep going for substantial periods of time – at least until the bell goes.

Secondly, every specification is overflowing with content, so it’s a struggle to get through everything in the time available. At the same time, many teachers find student involvement in learning very time-consuming - setting up activities, having the right equipment and generating the lesson ideas in the first place. It’s much easier to stand at the front and lecture. That way, at least, everyone in the class has a fair chance of picking up some of the important information, and the teacher can think to themselves “Well, I covered it all, if they haven’t learnt it, they’ve only got themselves to blame”.

Finally, much of the dominant ideas in educational policy have promoted specifications packed with knowledge, with an emphasis on recall in unseen examinations. The focus is on the traditional delivery of content, with students as ‘empty vessels’ waiting to be uncritically ‘filled up’ from the great repository of culture and knowledge.

It’s really no surprise that teachers talk a lot.

Why do students like listening?

OK, let’s face facts: a lot of the time, they’re not actually listening.

I did some very unscientific research a few years ago where I asked a sample of students the percentage of time they were actually paying attention when a teacher was talking. One Oxbridge applicant claimed 80% attention, but if you took him out of the equation, the average figure was around 30%.

So what are they doing when they appear to be listening? Teacher talk gives students the chance to sit and dream, to let their minds wander through the familiar adolescent dreams and fantasies. As long as they give the impression they're paying attention, no one will trouble them. Yes, there may be the odd question, but they bank on one of the two or three highly motivated ‘boffins’ to deal with those. Once one of them has answered correctly the teacher will assume that everyone else knows the answer too.

To maintain this pleasant equilibrium, students develop a range of skills. There are the individual nonverbal cues that indicate attentiveness. These include eye contact, pen holding, smiling and stationery fiddling. Another important skill is the ability for a few students to act as pathfinders - their job is to identify the teacher’s passions - the subjects on which they'll talk at length with precious little prompting and that can while away large swathes of lesson time. The passion may be Arsenal, antique door handles or Anne Boleyn, it doesn't matter. Once identified, students will be able to return to the issue at any point and prod the teacher into yet another monologue.

So teachers and students create a seen-but-unnoticed classroom consensus, an informal contract: “I (teacher) quite like talking, you (students) quite like avoiding demands being made of you. So I’ll talk, you be quiet – that way everyone’s happy. What’s the problem?”

What learning is going on while teachers are talking?

"I can’t recall any research suggesting that a lecture-style delivery is among the most effective methods."

If the teacher is talking on a relevant topic then some learning is almost certainly taking place. How much learning depends on the extent to which students are actively engaging with the talk. Are they making notes? Is questioning inclusive and regular? Are there examples, visual illustration, follow-up activities? I can’t recall any research suggesting that a lecture-style delivery is among the most effective methods. However, a short explanation of a key concept, difficult theory or an overview of a new topic can work very well if kept brief and followed up by student activities. As an Ofsted Inspector pointed out to me: “Whenever I enter a classroom I ask the question: who’s doing the work here? If the answer is the teacher, alarm bells go off.”

But there's a bigger issue for me. What does this style of ‘delivery’ tell students about power relationships? That the student is a passive and powerless receiver of information owned by their elders and betters. Their job is to listen, learn and obey. Questioning and challenging are just not part of it.

Of course many teachers are well aware of the issues here. They work hard to create and maintain the active engagement of students in learning and are often supported by management teams and by excellent resources. Qualifications like the Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) encourage students to define their own areas of learning and to manage their work independently, thus developing a broad range of skills that are far better preparation for life and work in the 21st century than the isolated chunks of knowledge that result from so many traditional exam courses.

Oops – I’ve just realised that this is a lecture on paper so I think I better stop now.

How can students take more ownership of the classroom?

1. Consider introducing courses that encourage students to define their own areas of learning and to manage their work independently. The EPQ (Extended Project Qualification) is one example.

2. Offer students (limited) choice over how they learn a particular topic.

3. Provide marking criteria and ask students to assess their own work. They are then able to identify the ways they need to improve.

4. Encourage students to reflect on the way they work and the methods of learning they employ. Spend a little time every lesson on this.

5. Build self-evaluation into classroom practice. At the end of lessons ask students what they learned and how their learning could be applied. Get them to write some questions they can use later in revision.

How do you promote student independence? Share your tips in the comments below.