I was watching a TV show with a medical aspect the other night; in it the doctor wanted to treat a patient whom the other characters didn’t like because he was a terrorist or something. The doctor said he had to treat the patient because he had vowed to ‘Do No Harm’, and not treating a patient goes against the Hippocratic Oath. My mind wandered during the TV show, as it often does when I’m at home in the evening, and I started to think about why teachers don’t have an equivalent. What if we had something similar, that we vowed to uphold even against conventional morality? What might it look like and how would it work in practice? What if we had The Pedagogic Oath?

With the new curriculum upon us, Rosemary Dewan of the Human Values Foundation explains how pupils can make terrific strides with an education that embraces hard skills, soft skills and intrapersonal skills...

Following extensive research (Lovat, Toomey and Clement, 2010, see below), education experts consider that “the best laid plans about the technical aspects of pedagogy are bound to fail unless the growth of the whole person – social, emotional, moral, spiritual and intellectual, is the pedagogical target”.

My to-do list during the summer holidays included preparing a number of collaborative problem-solving tasks (mysteries) for the new computing at schools (CAS) curriculum, KS2 and KS3. With my programming background, I focused on the computing science bit rather than information technology or digital literacy.

We’ve all experienced how languages borrow words when they come in contact with other languages. Cultures do the same thing, borrowing aspects of other cultures. If you take a job at an international school, you’re likely to experience a different school culture than you’re used to. It won’t be the culture of your host country, but it won’t be the culture of your home country either. And, if you’ve worked at other international schools before in other countries, it won’t quite match any of those either.

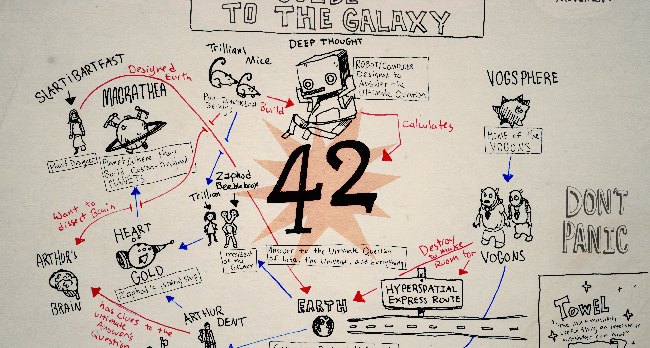

Chances are, you’ve read, listened to or seen a version of A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Here, teacher and author Lisa Jane Ashes applies themes and characters from Douglas Adams’ sci fi classic to look at how teachers can best create great questions.

Why 42? Douglas Adams’ classic The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is a great demonstration of how questioning can open up the imagination. Adams questioned everything we believe and a masterpiece of creativity was born. What if mice were more intelligent than men? What if the planet was created by technicians in a large factory? Underestimated dolphins, falling whales, improbability drives and the search for the ultimate answer to life, the universe and everything; this story is creativity at its maddest and best.

People sometimes mistake the concept of pupil engagement for frivolous, time-wasting fun. In fact, in any school staff room it’s likely that there will be at least one colleague shaking their head sadly and muttering the word “Edutainment” when particular classroom approaches are mentioned. The thing is, sometimes that cynicism is entirely reasonable; sometimes a wariness about “play” in the classroom is absolutely warranted. Why? Because there is an overwhelmingly important distinction between inspiring intrigue and engagement in a topic or skill, and simply sugar-coating the work with a meaningless, superficial “fun” activity.

It seems, at times, that SEN teaching might well be the most rewarding area of education. Some of these pupils have immense obstacles to overcome as part of their learning, and specialist teachers are always finding new and inventive ways to assist them. Carolyn Hughes, ICT leader at Meadowside Special School in Birkenhead, Merseyside, discusses the technological options available for making as many areas as SEN-accessible as possible.

Technology has a great role to play in improving access for learners with physical barriers to learning. For many with additional SEN, the assistive technology can be challenging itself; trying to make it personalised to the individual learner, to make is usable and purposeful. It should be asked, “What do we want the learners to do that they cannot do without assistive technology?”

Secondary and primary teachers across Wales have been faced with the challenge of embedding the Literacy and Numeracy Framework (LNF) into their whole school curriculums. Ambitious in scope, the LNF is a planning and assessment tool that maps key literacy and numeracy statements from the start of KS2 through to the end of KS3. Pupils will be assessed against the framework, as well as sitting annual national reading, numerical reasoning and numerical procedural tests every May.

A student’s behaviour in the classroom can be determined by a whole host of different factors, and their relationship with you as their classroom teacher is fundamentally the most important factor. However, in order to get good behaviour in a classroom with an individual, a lot more is needed than just sanctions and high expectations. This is where positive behaviour for learning comes in to play.

Back in September 2011, I began the academic year full of gusto. I had re-planned schemes of work, made some lovely new resources and prepared exciting performing and listening tasks. After several weeks into the term, I realised something wasn’t quite right. Work from some students hadn’t been done particularly well, feedback was becoming more lengthy and wordy, and the weaker students were continuing to make the same mistakes. I needed to rethink how I was teaching the struggling students.

A community-driven platform for showcasing the latest innovations and voices in schools

Pioneer House

North Road

Ellesmere Port

CH65 1AD

United Kingdom