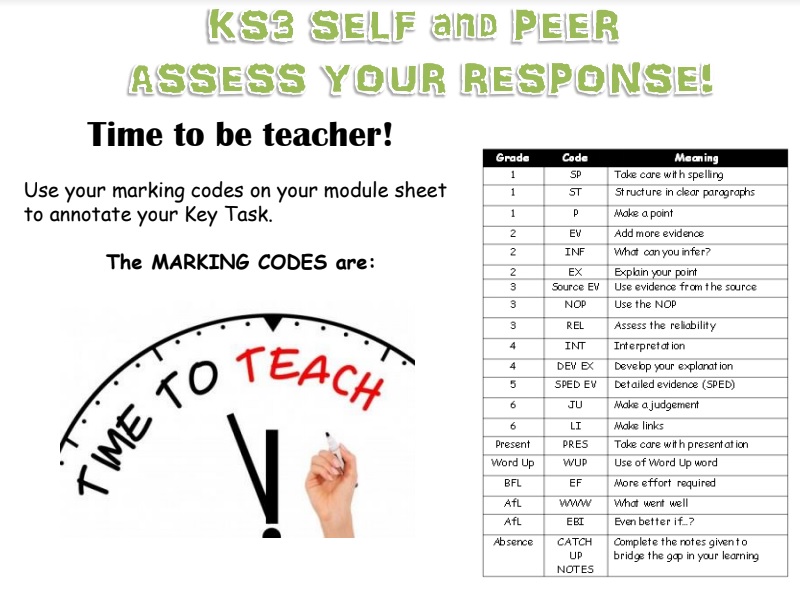

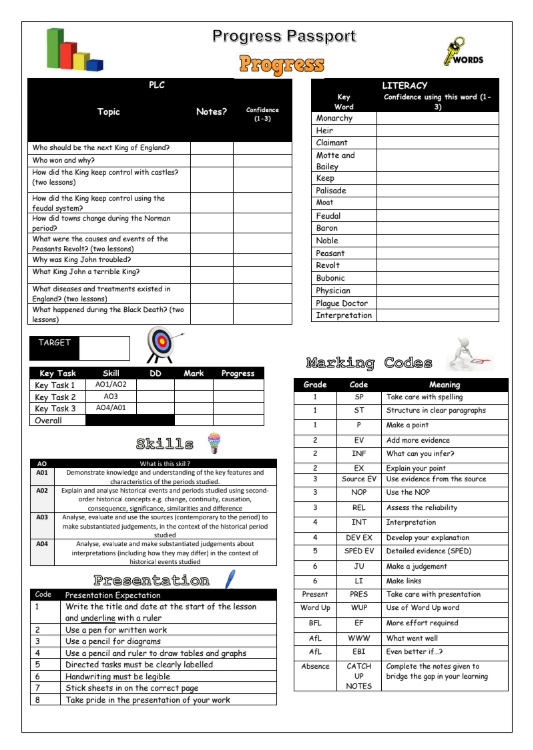

Coded marking is a practice that I have always used when assessing students’ work, as well as while facilitating both self and peer assessment. The basic premise is: rather than using a string of words or sentences, shorthand codes are used to represent certain skills or elements of the assessment criteria that either have or have not been met.

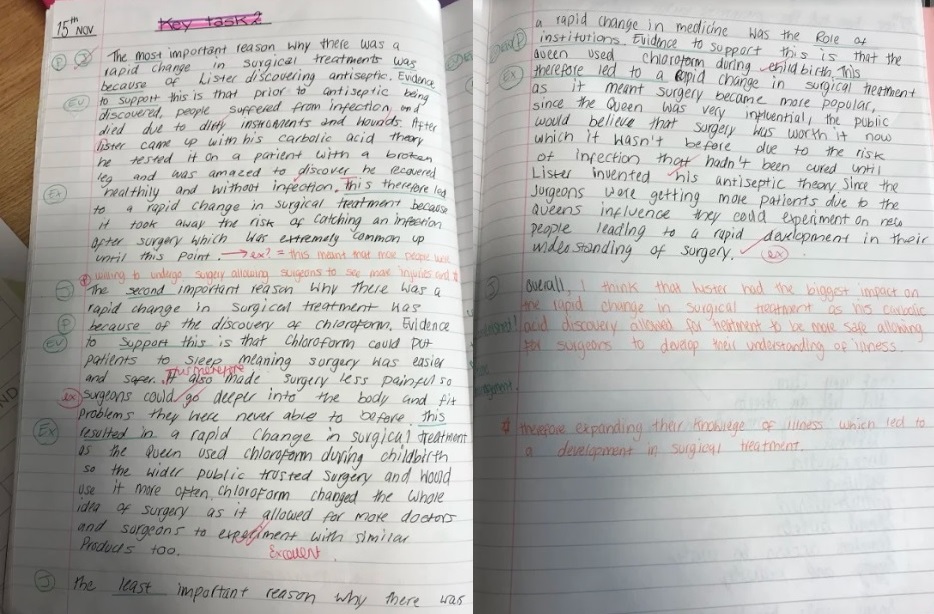

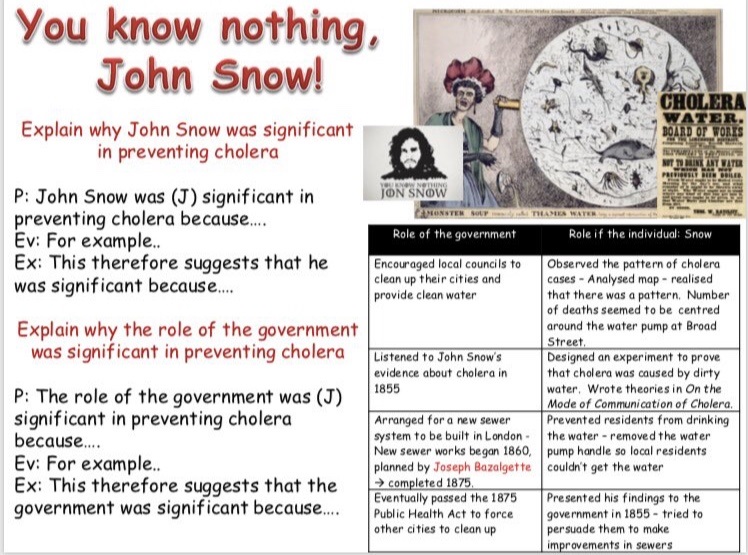

For example, a simple PEE chain can be identified by the use of P, Ev, Ex or, if that criteria is missing, P? Ev? Ex? By doing so, it not only saves the person marking it time “This method speeds up marking.”(not having to write out long words or sentences repeatedly), but it also creates a very clear and stark code - which is easier to understand and digest - in the margin. Within the remit of teaching, it speeds up marking, helps to pinpoint a level in which the students’ work resides, and means that standardisation across the department can be undertaken in a much more consistent and coherent way.

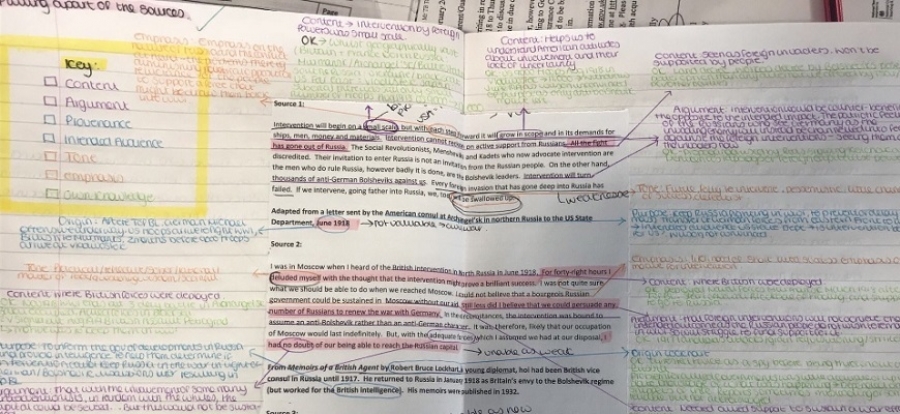

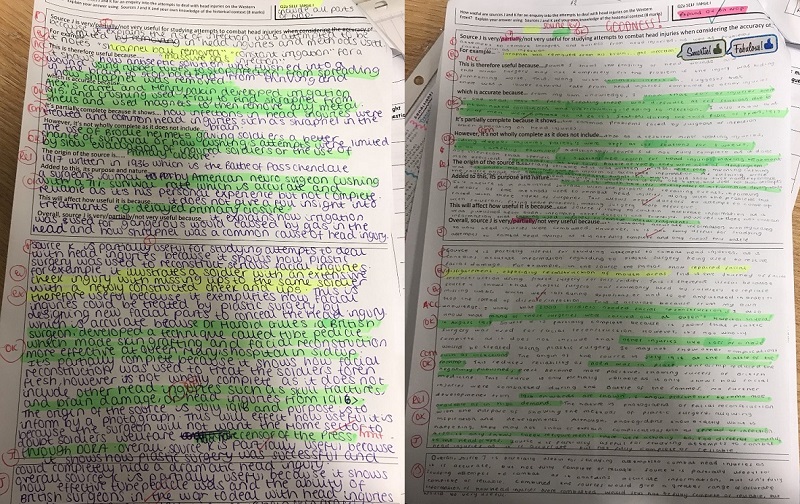

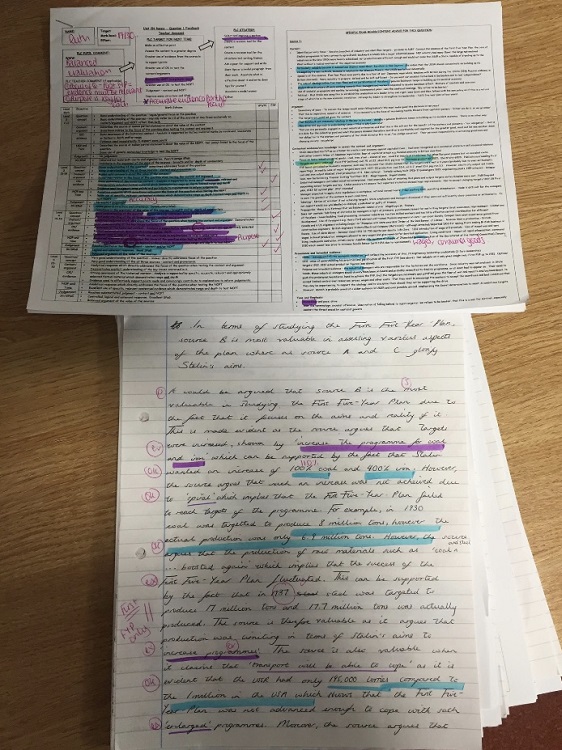

For students, especially lower-ability and SEND, it enables them to understand the assessment and skill criteria far easier, as the codes are easier to digest and translate into feedback steps that need to be taken. This has been very evident when practicing source utility skills, which require students to assess how useful a source is by evaluating its accuracy, completeness and reliability. By using the codes, students are able to rapidly plan, structure, write and self/peer assess or receive feedback, as the condensed shorthand codes in the margin locate inclusion.

(Original PDF here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dKqJXyJ5mL0H-_gDLzT7LIDh7h3Hl09v/view?usp=sharing)

(Original PDF here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dKqJXyJ5mL0H-_gDLzT7LIDh7h3Hl09v/view?usp=sharing)

As a big advocate of self and peer assessment, it also means that students are able to mark and reflect upon their work independently by identifying, for themselves, where certain elements have and have not been included. This can be applied to marking their own work, model answers or even planning questions when they consider the reasons for an event and use the codes to create a PEE chain plan.

Some may raise eyebrows and question how applicable this is with lower-ability, SEND, EAL or lower Key Stage 3 students. However, I use this practice with all year groups and all abilities, as does the rest of my department who now, as part of our new departmental policy, use these to assess and provide feedback.

With scaffolding, clear explanations, consistency and repetition, students improve their knowledge of the codes and what that criteria looks like in reality. EAL students actually find it easier to interpret and use the codes than longer-hand feedback or prose-heavy level criteria.

That’s not to say that, the first few times they mark their own work, a lower-ability student won’t mark EV for evidence when there is none, confusing what they think is evidence with something teachers and examiners know is not. Yet, with continued coaching, application and discussion of the criteria, and with examples on the board, over time their understanding of it improves. Students become able to assess their work accurately and more effectively.

This has had a massive impact upon the learning in my classroom. Students identify for themselves where they have and have not met the criteria and thus take ownership over their improvements and next steps as they have not been “shown” what is wrong and led to it blindly. They instead know for themselves where that is and can recognise it for themselves. This not only makes for more reflective learning; it also supports them when they are writing answers. You can see students actively assess their work and correct it for themselves, before submitting it as a final piece of work. They are drafting and improving for themselves, and not relying or depending upon the teacher to underline, highlight and circle it in red pen so that they notice where an error is.

A student self-assessed his 'Key Task' assessment and corrected it before submitting it for teacher assessment. This way, they reflected and self-identified where improvements needed to be made without being led to it, lessening dependency. I then mark their work, checking their coding as I go, and provide further feedback if required. 7/10 the students hit the nail on the head and have already improved everything I would have suggested!

A student self-assessed his 'Key Task' assessment and corrected it before submitting it for teacher assessment. This way, they reflected and self-identified where improvements needed to be made without being led to it, lessening dependency. I then mark their work, checking their coding as I go, and provide further feedback if required. 7/10 the students hit the nail on the head and have already improved everything I would have suggested!

Interested by this, I carried out research to see if others used this practice. The Education Endowment Foundation website had information about one project which had carried out research and development into this practice. It concluded that there “With continued coaching, students’ understanding improves.”had been no impact through their findings: “Research suggests that there is no difference between the effectiveness of coded or uncoded feedback, providing that pupils understand what the codes mean”, which added to “One study of undergraduates even found that providing the correct answer to mistakes was no more effective than not marking the work at all. It is suggested that providing the correct answer meant that pupils were not required to think about mistakes they had made, or recall their existing knowledge, and as a result were no less likely to repeat them in the future.”

I interpret this as: using longer sentences and feedback, instead of shorthand codes, has no additional benefit (so why do it and waste that time which could be spent planning?). Also, if we write all of the answers there for them, we will not be supporting reflective and independent learning. Instead, it is better to enable them to pinpoint their own errors in an accessible and easy-to-use way, so that they are less likely to repeat these mistakes as they have been required to think about the work for themselves.

Source utility and the structure is a skill which can be difficult to teach students. The codes provides them with stepping stones so that they know where each criteria belongs and this means when they write and assess their work, they're able to see if they have or have not included certain elements.

Source utility and the structure is a skill which can be difficult to teach students. The codes provides them with stepping stones so that they know where each criteria belongs and this means when they write and assess their work, they're able to see if they have or have not included certain elements.

If you’re interested in trying or honing this practice, here are some practical tips to get started:

1. Clear, simple codes. They need to be shorthand and simple to apply.

2. Linked to an assessment, skills or content criteria. This enables both yourself and the students to see the purpose of the inclusion of certain elements into their work. It also promotes effective self-assessment, teacher assessment and standardisation across the department, as levels in work can be pinpointed more easily. When used with marking feedback sheets and ‘examiner reports’ which I create - noting content they should and could have included - this then enables students to understand why their work received the mark it did, as well as allowing them to correct their work.

3. Consistency. Do not chop and change them randomly or in an ad-hoc manner. Create a code and see it through. If it doesn’t work, then refine and change this at a later appropriate time, to avoid confusion and loss of faith in the codes.

4. Repetition. The more you and the students use them, the more successful this practice becomes.

5. Effective scaffolding and coaching. Students will need support at the start to understand the codes, know what that criteria looks like when it is properly applied, and so on. Some may take longer than others and require more scaffolding, but effective planning of these lessons will overcome this challenge.

6. Patience. With this comes patience. Some classes immediately take to this practice and effectively use them. Some take longer. Patience and consistency is key.

7. Motivation and purpose. Students need to ‘buy into’ the practice themselves; motivate them, share the benefits so that they too realise it, and praise them when they use it.

Want to receive cutting-edge insights from leading educators each week? Sign up to our Community Update and be part of the action!