At the time, I always thought it was the personalities that had me enraptured. Looking back, there were more subtle forces at work; it was also the hidden history weaved in with such craft that had me entranced. Without realising it, I was being transported back in time to these different eras and I was discovering more about the past with every sentence. Fictional books are a window into the past.

The growth of technology has resulted in many benefits, especially for the learning of students. They can now access information about the past within seconds and discover more about topics that they study. Similarly to me as a child, they can now read books on their tablets, and embrace the same stories I too read. However, a sentimental side of me was awoken when a student questioned what the purpose was of paper books in this modern age. "Fictional books are a window into the past."While no Luddite, a part of me felt saddened that there couldn’t be a coexistence of technology and paper books - each have their own merits, surely? The tangibility of paper, the turning and folding of pages and the smell of a good book can help enliven the senses and evoke the past in a different way to technology. Perhaps students hadn’t quite connected with paper books the way that older generations had.

A few weeks later, with this buzzing around in my head, a few Year 8 students shared that they had been studying Animal Farm. Fantastic, I thought. A chance to discuss with them their opinions of Communism and dictatorship, a topic we were due to study later in the year. However, while there was a loose general understanding of a “nasty ruler” and “control”, the core concepts and subtle nuances hadn’t quite rung home for the students. The history within the text had not come to life for them and they were shocked to find out that this “story” was actually a novella evaluating the impact of the Russian Revolution and resulting Communist dictatorship. Perhaps there was the chance for a learning opportunity here?

Bringing the past to life…

I devised a cross-curricular project-based learning (PBL) idea that would involve Year 8 students exploring the hidden history within fictional texts in their History and English lessons. The essential question was ‘How can fictional books bring the past to life?’. It was an attempt to double up on two aspects of learning that I wanted to explore:

- What were the historical themes within fictional books? How can they bring the past to life for our students and allow them to step back in time to understand the periods better?

- What purpose do paper books have?

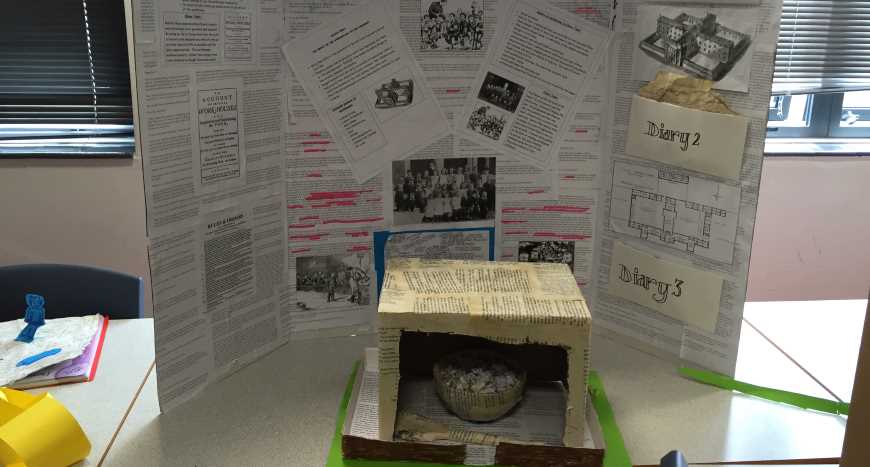

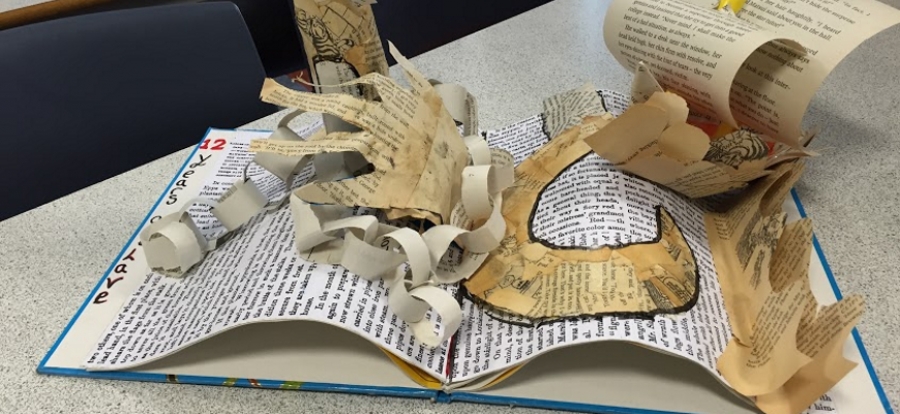

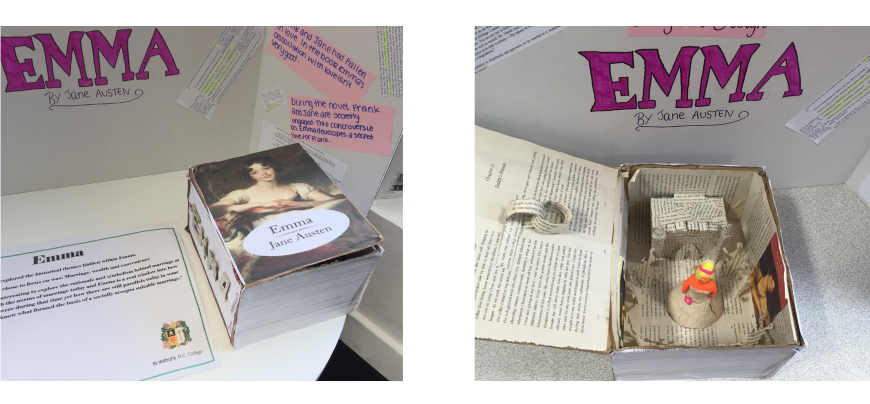

The proposed idea was that students would work in collaborative groups to research a book and draw out the historical themes within it. From that, the project demanded from them that they communicate and showcase these themes using old, re-purposed books; they were being asked to upcycle old books in order to create their understanding of the past that was hidden in their books.

I decided that the best approach to this was to also use a cross-curricular approach. "It could be littered with many ‘learning from our mistakes’ moments!"Deep learning has a greater chance of occurring if we encourage students to apply their knowledge across the varying subjects that they study as this synthesis will embed within them the culture of transferable skills and knowledge.

The result was a project that involved six lessons using a PBL approach. The staff involved attended training sessions led by myself. They had the opportunity to collaboratively plan the scheme of work, as well as input different ideas with regard to which books fit best with their curricula but also provided interesting inference into the historical backdrop. The hope was that by doing so, each teacher had the skills and confidence to deliver this new approach to learning, as we had never trialled anything like this before our school. It was all going to be very new, and we knew that with this being the first PBL, it could be littered with many, to be politely put, ‘learning from our mistakes’ moments!

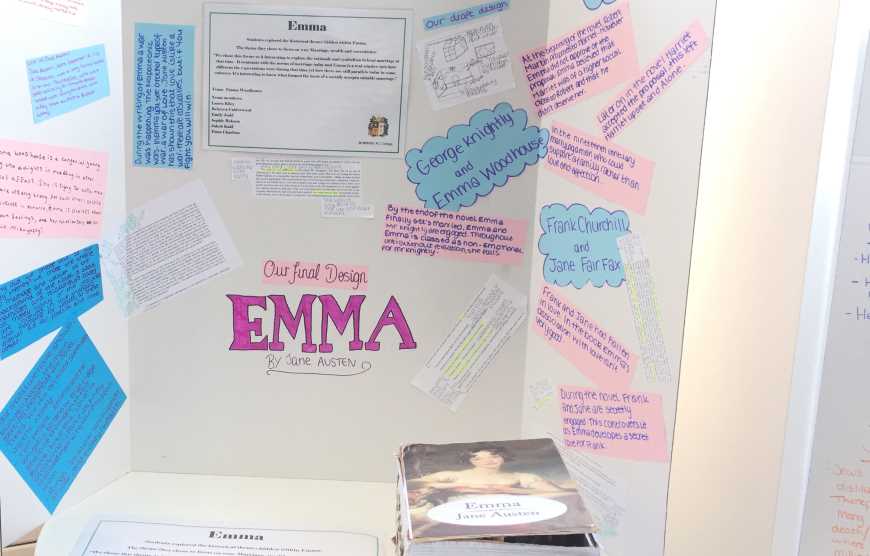

In differentiated groups, the students worked collaboratively to research the book they had been given. Each group had a different book to allow for both a range of interests and differentiation. It was great to see that the students were discovering new moments within the books. They read aloud lines from texts to each other they may have previously studied but instead used inference skills to tease out the historical subtleties that they may have glazed over. Excited by the new ideas they were coming across, they began to research further the historical period within the text, based upon the inferences they had made. Why did Jane Austen’s Emma have such perceptions about class and marriage? What might this tell us about Victorian values and the position of women at this time? What about The Great Gatsby? What can this tell us about prosperity in 1920s America or the impact of Prohibition on society? Cue a flurry of research into what Prohibition was and why it was introduced, while listening to jazz music.

The fantastic thing about PBL is the independent learning aspect of it, in that the students were self-motivating and being resourceful, with minimal guidance from teachers. As a “facilitator”, all it required was to check in on the students and clarify any misconceptions. Aside from that, the students were busy finding their own information, determining their chosen theme, drafting, reviewing and planning for their next steps. Their student booklet contained an overview plan where they would create their own success criteria, set goals and timeframes, divvy out jobs and responsibilities as well as plan their resources.

From there, the project took off. Students boiled down their range of themes in their groups having deconstructed, annotated and researched their books. What was great about it was that, while they were reading paper texts of the books, they were using both resources in the classroom as well as new technology to research the themes within them. They were buddied up with academics such as Dr Angela Smith from Sunderland University, who acted as mentors through email discussions and experts in linguistics and discourse who could help to tease out nuances in the texts through questioning.

Through peer discussions and presentations within their groups, they finalised their chosen historical theme from within the book and drafted potential ideas about how they could repurpose the books to communicate this. Once chosen, they each drafted their own ideas of how to communicate it, selected their best one, and asked other groups to peer review them to identify strengths and areas for development before the crafting began.

What occurred during the creation phase was a buzz of engagement and excitement that I could never have anticipated! Students were active in bringing in old books which they had long neglected, and had even visited friends, neighbours and local charity shops to gather them. They were animated in lessons, operated as a collaborative machine, and you could actually physically see and feel the sense of purpose and pride in what they were creating.

It was interesting to watch them as they set out with high expectations of what they wanted to achieve, but had to learn to be resilient when certain ideas couldn’t come to fruition and so they had to adapt plans and devise solutions; again, free from teacher hand-holding. How could you make the fence between Bruno and Shmuel stand up? Realising that building a galleon ship couldn’t happen within the timeframe, and wasn’t actually going to tell the full story of Solomon Northup, resulted in the evolution of the idea into creating a smaller ship sailing through the pages to a chained and uncertain future; an idea they now much preferred compared to their proposed. They were failing, learning from it, and succeeding.

The final products were innovative, creative and well-thought out. The students had put real thought into their chosen designs and had ensured that they were effectively communicated the period given. They had transitioned from having no paper-crafting skills to learning them all by themselves. They had produced ships, flowers and a book itself. Meanwhile, they could talk knowledgeably about the history within the book and what we can learn from the texts about it, including the value of historical fiction books as sources. This was all through collaborative endeavour to meet tight deadlines. Once completed, the students had their own in school gallery where they looked at one another’s creations and reviewed them. Following this, they were installed at the University of Sunderland in an exhibit over the summer, where parents were invited to see them on display. It was great to see the pride that they felt in having accomplished so much, and having done so in such an independent way. Reflecting on the project, a part of me felt enlivened by the fact that paper books had proven their worth as an item that can still hold its own in the twenty-first century, and that the students had sensed the purpose of using it in tandem with modern technology. More so, I felt assured that the students were now more acutely aware that the history within these books are not just a backdrop for a story, but more a window into the past that they can learn so much from. Through crafting the pages to communicate the history, they realised that the authors had done the same; they had crafted the past into their fictional books to communicate about this period. As a teacher/facilitator I learned a lot from the process too. I realised it was safe to let go of the reigns, to trust that with the correct planning and structure that the students could take charge of their own learning and succeed and produce learning that I could never have allowed for had I forced them down by pre-determined planned route with rigid desired outcomes. So, in answer to the question, how can fictional books bring the past to life? Through inference, collaboration, research….. and a lot of PVA glue! Do you use PBL to similar effect? Share your experiences below.